Sinbad the Sailor

Sinbad the Sailor (/ˈsɪnbæd/; Arabic: سندباد البحري, romanized: Sindibādu l-Bahriyy or Sindbad) is a fictional mariner and the hero of a story-cycle. He is described as hailing from Baghdad during the early Abbasid Caliphate (8th and 9th centuries A.D.). In the course of seven voyages throughout the seas east of Africa and south of Asia, he has fantastic adventures in magical realms, encountering monsters and witnessing supernatural phenomena.

Origins and sources[edit]

The tales of Sinbad are a relatively late addition to the One Thousand and One Nights – they do not feature in the earliest 14th-century manuscript, and they appear as an independent cycle in 18th- and 19th-century collections. The tale reflects the trend within the Abbasid realm of Arab and Muslim sailors exploring the world. The stories display the folk and themes present in works of that time. The Abbasid reign was known as a period of great economic and social growth. Arab and Muslim traders would seek new trading routes and people to trade with. This process of growth is reflected in the Sinbad tales. The Sinbad stories take on a variety of different themes. Later sources include Abbasid works such as the "Wonders of the Created World", reflecting the experiences of 13th century Arab mariners who braved the Indian Ocean.[1]

The Sinbad cycle is set in the reign of the Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid (786–809). The Sinbad tales are included in the first European translation of the Nights, Antoine Galland's Les mille et une nuits, contes arabes traduits en français, an English edition of which appeared in 1711 as The new Arabian winter nights entertainments[2] and went through numerous editions throughout the 18th century.

The earliest separate publication of the Sinbad tales in English found in the British Library is an adaptation as The Adventures of Houran Banow, etc. (Taken from the Arabian Nights, being the third and fourth voyages of Sinbad the Sailor.),[3] around 1770. An early US edition, The seven voyages of Sinbad the sailor. And The story of Aladdin; or, The wonderful lamp, was published in Philadelphia in 1794.[4] Numerous popular editions followed in the early 19th century, including a chapbook edition by Thomas Tegg. Its best known full translation was perhaps as tale 120 in Volume 6 of Sir Richard Burton's 1885 translation of The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night.[5][6][7]

Tales[edit]

Sinbad the Porter and Sinbad the Sailor[edit]

Like the 1001 Nights, the Sinbad story-cycle has a frame story which goes as follows: in the days of Harun al-Rashid, Caliph of Baghdad, a poor porter (one who carries goods for others in the market and throughout the city) pauses to rest on a bench outside the gate of a rich merchant's house, where he complains to God about the injustice of a world which allows the rich to live in ease while he must toil and yet remain poor. The owner of the house hears and sends for the porter, finding that they are both named Sinbad. The rich Sinbad tells the poor Sinbad that he became wealthy "by Fortune and Fate" in the course of seven wondrous voyages, which he then proceeds to relate.

First Voyage[edit]

After dissipating the wealth left to him by his father, Sinbad goes to sea to repair his fortune. He sets ashore on what appears to be an island, but this island proves to be a gigantic sleeping whale on which trees have taken root ever since the whale was young. Awakened by a fire kindled by the sailors, the whale dives into the depths, the ship departs without Sinbad, and Sinbad is only saved by a passing wooden trough sent by the grace of God. He is washed ashore on a densely wooded island. While exploring the deserted island, he comes across one of the king's grooms. When Sinbad helps save the king's mare from being drowned by a sea horse (not a seahorse, but a supernatural horse that lives underwater), the groom brings Sinbad to the king. The king befriends Sinbad, and he rises in the king's favor and becomes a trusted courtier. One day, the very ship on which Sinbad set sail docks at the island, and he reclaims his goods (still in the ship's hold). Sinbad gives the king his goods and in return the king gives him rich presents. Sinbad sells these presents for a great profit. Sinbad returns to Baghdad, where he resumes a life of ease and pleasure. With the ending of the tale, Sinbad the sailor makes Sinbad the porter a gift of a hundred gold pieces and bids him return the next day to hear more about his adventures.

Second Voyage[edit]

On the second day of Sinbad's tale-telling (but the 549th night of Scheherazade's), Sinbad the sailor tells how he grew restless of his life of leisure, and set to sea again, "possessed with the thought of traveling about the world of men and seeing their cities and islands." Accidentally abandoned by his shipmates again, he finds himself stranded in an island which contains roc eggs. He attaches himself with the help of his turban to a roc and is transported to a valley of giant snakes which can swallow elephants; these serve as the rocs' natural prey. The floor of the valley is carpeted with diamonds, and merchants harvest these by throwing huge chunks of meat into the valley: the birds carry the meat back to their nests, and the men drive the birds away and collect the diamonds stuck to the meat. The wily Sinbad straps one of the pieces of meat to his back and is carried back to the nest along with a large sack full of precious gems. Rescued from the nest by the merchants, he returns to Baghdad with a fortune in diamonds, seeing many marvels along the way.

Third Voyage[edit]

Sinbad sets sail again from Basra. But by ill chance, he and his companions are cast up on an island where they are captured by a "huge creature in the likeness of a man, black of colour, ... with eyes like coals of fire and large canine teeth like boar's tusks and a vast big gape like the mouth of a well. Moreover, he had long loose lips like camel's, hanging down upon his breast, and ears like two Jarms falling over his shoulder-blades, and the nails of his hands were like the claws of a lion." This monster begins eating the crew, beginning with the Reis (captain), who is the fattest. (Burton notes that the giant "is distinctly Polyphemus".)

Sinbad hatches a plan to blind the beast with the two red-hot iron spits with which the monster has been kebabbing and roasting the ship's company. He and the remaining men escape on a raft they constructed the day before. However, the giant's mate hits most of the escaping men with rocks and they are killed. After further adventures (including a gigantic python from which Sinbad escapes using his quick wits), he returns to Baghdad, wealthier than ever.

Fourth Voyage[edit]

Impelled by restlessness, Sinbad takes to the seas again and, as usual, is shipwrecked. The naked savages amongst whom he finds himself feed his companions a herb which robs them of their reason (Burton theorises that this might be bhang), prior to fattening them for the table. Sinbad realises what is happening and refuses to eat the madness-inducing plant. When the cannibals lose interest in him, he escapes. A party of itinerant pepper-gatherers transports him to their own island, where their king befriends him and gives him a beautiful and wealthy wife.

Too late Sinbad learns of a peculiar custom of the land: on the death of one marriage partner, the other is buried alive with his or her spouse, both in their finest clothes and most costly jewels. Sinbad's wife falls ill and dies soon after, leaving Sinbad trapped in a cavern, a communal tomb, with a jug of water and seven pieces of bread. Just as these meagre supplies are almost exhausted, another couple—the husband dead, the wife alive—are dropped into the cavern. Sinbad bludgeons the wife to death and takes her rations.

Such episodes continue; soon he has a sizable store of bread and water, as well as the gold and gems from the corpses, but is still unable to escape, until one day a wild animal shows him a passage to the outside, high above the sea. From here, a passing ship rescues him and carries him back to Baghdad, where he gives alms to the poor and resumes his life of pleasure.

Burton's footnote comments: "This tale is evidently taken from the escape of Aristomenes the Messenian from the pit into which he had been thrown, a fox being his guide. The Arabs in an early day were eager students of Greek literature." Similarly, the first half of the voyage resembles the Circe episode in The Odyssey, with certain differences: while a plant robs Sinbad's men of their reason in the Arab tales, it is Circe's magic which "fattened" Odysseus' men in The Odyssey. It is in an earlier episode, featuring the 'Lotus Eaters', that Odysseus' men are fed a similar magical fruit which robs them of their senses.

Fifth Voyage[edit]

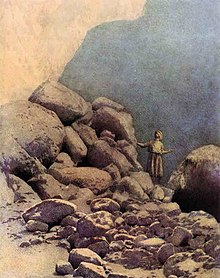

.jpg/220px-Sinbad_the_Sailor_(5th_Voyage).jpg)

"When I had been a while on shore after my fourth voyage; and when, in my comfort and pleasures and merry-makings and in my rejoicing over my large gains and profits, I had forgotten all I had endured of perils and sufferings, the carnal man was again seized with the longing to travel and to see foreign countries and islands." Soon at sea once more, while passing a desert island Sinbad's crew spots a gigantic egg that Sinbad recognizes as belonging to a roc. Out of curiosity, the ship's passengers disembark to view the egg, only to end up breaking it and having the chick inside as a meal. Sinbad immediately recognizes the folly of their behaviour and orders all back aboard ship. However, the infuriated parent rocs soon catch up with the vessel and destroy it by dropping giant boulders they have carried in their talons.[8]

Shipwrecked yet again, Sinbad is enslaved by the Old Man of the Sea, who rides on his shoulders with his legs twisted round Sinbad's neck and will not let go, riding him both day and night until Sinbad would welcome death. (Burton's footnote discusses possible origins for the old man—the orang-utan, the Greek god Triton—and favours the African custom of riding on slaves in this way).[9]

Eventually, Sinbad makes wine and tricks the Old Man into drinking some. Sinbad kills him after he falls off. A ship carries him to the City of the Apes, a place whose inhabitants spend each night in boats off-shore, while their town is abandoned to man-eating apes. Yet through the apes, Sinbad recoups his fortune and eventually finds a ship which takes him home once more to Baghdad.

Sixth Voyage[edit]

"My soul yearned for travel and traffic". Sinbad is shipwrecked yet again, this time quite violently as his ship is dashed to pieces on tall cliffs. There is no food to be had anywhere, and Sinbad's companions die of starvation until only he is left. He builds a raft and discovers a river running out of a cavern beneath the cliffs. The stream proves to be filled with precious stones and it becomes apparent that the island's streams flow with ambergris. He falls asleep as he journeys through the darkness and awakens in the city of the king of Serendib (Sri Lanka/Ceylon), "diamonds are in its rivers and pearls are in its valleys". The king marvels at what Sinbad tells him of the great Haroun al-Rashid, and asks that he take a present back to Baghdad on his behalf, a cup carved from a single ruby, with other gifts including a bed made from the skin of the serpent that swallowed an elephant[a] ("And whoso sitteth upon it never sickeneth"), and "A hundred thousand miskals of Sindh lign-aloesa.", and a slave-girl "like a shining moon". Sinbad returns to Baghdad, where the Caliph wonders greatly at the reports Sinbad gives of Serendib.

Seventh and Last Voyage[edit]

The ever-restless Sinbad sets sail once more, with the usual result. Cast up on a desolate shore, he constructs a raft and floats down a nearby river to a great city. Here the chief of the merchants gives Sinbad his daughter in marriage, names him his heir, and conveniently dies. The inhabitants of this city are transformed once a month into birds, and Sinbad has one of the bird-people carry him to the uppermost reaches of the sky, where he hears the angels glorifying God, "whereat I wondered and exclaimed, 'Praised be God! Extolled be the perfection of God!'" But no sooner are the words out than there comes fire from heaven which all but consumes the bird-men. The bird-people are angry with Sinbad and set him down on a mountain-top, where he meets two youths, servants of God who give him a golden staff; returning to the city, Sinbad learns from his wife that the bird-men are devils, although she and her father were not of their number. And so, at his wife's suggestion, Sinbad sells all his possessions and returns with her to Baghdad, where at last he resolves to live quietly in the enjoyment of his wealth, and to seek no more adventures.

Burton includes a variant of the seventh tale, in which Haroun al-Rashid asks Sinbad to carry a return gift to the king of Serendib. Sinbad replies, "By Allah the Omnipotent, Oh my lord, I have taken a loathing to wayfare, and when I hear the words 'Voyage' or 'Travel,' my limbs tremble". He then tells the Caliph of his misfortune-filled voyages; Haroun agrees that with such a history "thou dost only right never even to talk of travel". Nevertheless, at the Caliph's command, Sinbad sets forth on this, his uniquely diplomatic voyage. The king of Serendib is well pleased with the Caliph's gifts (which include, among other things, the food tray of King Solomon) and showers Sinbad with his favour. On the return voyage, the usual catastrophe strikes: Sinbad is captured and sold into slavery. His master sets him to shooting elephants with a bow and arrow, which he does until the king of the elephants carries him off to the elephants' graveyard. Sinbad's master is so pleased with the huge quantities of ivory in the graveyard that he sets Sinbad free, and Sinbad returns to Baghdad, rich with ivory and gold. "Here I went in to the Caliph and, after saluting him and kissing hands, informed him of all that had befallen me; whereupon he rejoiced in my safety and thanked Almighty Allah; and he made my story be written in letters of gold. I then entered my house and met my family and brethren: and such is the end of the history that happened to me during my seven voyages. Praise be to Allah, the One, the Creator, the Maker of all things in Heaven and Earth!".

Some versions return to the frame story, in which Sinbad the Porter may receive a final generous gift from Sinbad the Sailor. In other versions the story cycle ends here, and there is no further mention of Sinbad the Porter.

Adaptations[edit]

Sinbad's quasi-iconic status in Western culture has led to his name being recycled for a wide range of uses in both serious and not-so-serious contexts, frequently with only a tenuous connection to the original tales. Many films, television series, animated cartoons, novels, and video games have been made, most of them featuring Sinbad not as a merchant who stumbles into adventure, but as a dashing dare-devil adventure-seeker.

Films[edit]

English language animated films[edit]

- Sinbad the Sailor (1935) is an animated short film produced and directed by Ub Iwerks.

- Popeye the Sailor Meets Sindbad the Sailor (1936) is a two-reel animated cartoon short subject in the Popeye Color Feature series, produced in Technicolor and released to theatres on 27 November 1936 by Paramount Pictures.[10] It was produced by Max Fleischer for Fleischer Studios, Inc. and directed by Dave Fleischer.

- Sinbad (1992) is an animated film originally released on 18 May 1992 and based on the classic Arabian Nights tale, Sinbad the Sailor, and produced by Golden Films.

- Sinbad: Beyond the Veil of Mists (2000) is the first feature-length computer animation film created exclusively using motion capture.[11] While many animators worked on the project, the human characters were entirely animated using motion capture.

- Sinbad: Legend of the Seven Seas (2003) is an American animated adventure film produced by DreamWorks Animation and distributed by DreamWorks Pictures. The film uses traditional animation and computer animation. It was directed by Tim Johnson.

Non-English language animated films[edit]

- Arabian naito: Shindobaddo no bôken (Arabian Nights: Adventures of Sinbad) (1962) (animated Japanese film).

- A Thousand and One Nights (1969) Story created by Osamu Tezukui, combination of other One Thousand and One Nights stories and the legends of Sinbad.

- Pohádky Tisíce a Jedné Noci (Tales of 1,001 Nights) (1974), a seven-part animated film by Karel Zeman.

- Doraemon: Nobita's Dorabian Nights[12] (1991).

- Sinbad (film trilogy) (2015–2016) is a series of Japanese animated family adventure films produced by Nippon Animation and Shirogumi.

- The Adventures of Sinbad (2013) is an Indian 2D animated film directed by Shinjan Neogi and Abhishek Panchal, and produced by Afzal Ahmed Khan.[13]

- Sinbad: Pirates of Seven Storm (2016) A Russian animated film by CTB Film Company.

Live-action English language films[edit]

- Arabian Nights is a 1942 adventure film directed by John Rawlins and starring Sabu, Maria Montez, Jon Hall and Leif Erickson. The film is derived from The Book of One Thousand and One Nights but owes more to the imagination of Universal Pictures than the original Arabian stories. Unlike other films in the genre (The Thief of Bagdad), it features no monsters or supernatural elements.[14]

- Sinbad the Sailor (1947) is a 1947 American Technicolor fantasy film directed by Richard Wallace and starring Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Maureen O'Hara, Walter Slezak, and Anthony Quinn. It tells the tale of the "eighth" voyage of Sinbad, wherein he discovers the lost treasure of Alexander the Great.

- Son of Sinbad (1955) is a 1955 American adventure film directed by Ted Tetzlaff. It takes place in the Middle East and consists of a wide variety of characters including over 127 women.

- The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) is a 1958 Technicolor heroic fantasy adventure film directed by Nathan H. Juran and starring Kerwin Mathews, Torin Thatcher, Kathryn Grant, Richard Eyer, and Alec Mango. It was distributed by Columbia Pictures and produced by Charles H. Schneer.[15]

- Captain Sindbad (1963) is a 1963 independently made fantasy and adventure film, produced by Frank King and Herman King (King Brothers Productions), directed by Byron Haskin, that stars Guy Williams and Heidi Brühl. The film was shot at the Bavaria Film studios in Germany and was distributed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.[16]

- The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973) a fantasy film directed by Gordon Hessler and featuring stop motion effects by Ray Harryhausen. It is the second of three Sinbad films released by Columbia Pictures.

- Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977) is a fantasy film directed by Sam Wanamaker and featuring stop motion effects by Ray Harryhausen. The film stars Patrick Wayne, Taryn Power, Margaret Whiting, Jane Seymour, and Patrick Troughton. It is the third and final Sinbad film released by Columbia Pictures.

Live-action English language direct-to-video films[edit]

- Sinbad: The Battle of the Dark Knights (1998) – DTV film about a young boy that must go back in time to help Sinbad.

- The 7 Adventures of Sinbad (2010) is an American adventure film directed by Adam Silver and Ben Hayflick. As a mockbuster distributed by The Asylum, it attempts to capitalise on Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time and Clash of the Titans.[17]

- Sinbad and The Minotaur (2011) starring Manu Bennett is a 2011 Australian fantasy B movie directed by Karl Zwicky serving as an unofficial sequel to the 1947 Douglas Fairbanks Jr. film and Harryhausen's Sinbad trilogy.[18] It combines Arabian Nights hero Sinbad the Sailor with the Greek legend of the Minotaur.[19]

- Sinbad: The Fifth Voyage (2014) starring Shahin Sean Solimon, low-budget film.

- Sinbad and the War of the Furies (2016) An American action film starring John Hennigan, direct-to-streaming.

Live-action non-English language films[edit]

- Sinbad Khalashi, or Sinbad the Sailor is a 1930 Indian silent action-adventure film by Ramchandra Gopal Torney.[20]

- Sinbad Jahazi, or Sinbad the Sailor, is a 1952 Indian Hindi-language adventure film by Nanabhai Bhatt.[20]

- Sindbad ki Beti, or Daughter of Sindbad, is a 1958 Indian Hindi-language fantasy film by Ratilal. It follows the daughter of Sindbad as she goes out in search for her missing father.[20]

- Son of Sinbad is a 1958 Indian Hindi-language film by Nanabhai Bhatt. A sequel to Sinbad Jahazi, it follows the adventures of the son of Sinbad in high seas.[20]

- Sinbad contro i sette saraceni (Sinbad against the Seven Saracens). (Italian: Sindbad contro i sette saraceni, also known as Sinbad Against the 7 Saracens) is a 1964 Italian adventure film written and directed by Emimmo Salvi and starring Gordon Mitchell.[21][22] The film was released straight to television in the United States by American International Television in 1965.

- Sindbad Alibaba and Aladdin is a 1965 Indian Hindi-language fantasy-adventure musical film by Prem Narayan Arora. It starred Pradeep Kumar in the role of Sindbad.[20]

- Shehzade Sinbad kaf daginda (Prince Sinbad of the Mountains) (1971) (Turkish film).

- Simbad e il califfo di Bagdad (Sinbad and the Caliph of Baghdad) (1973) (Italian film).

- Sinbad of the Seven Seas (1989) is a 1989 Italian fantasy film produced and directed by Enzo G. Castellari from a story by Luigi Cozzi, revolving around the adventures of Sinbad the Sailor. Sinbad must recover five magical stones to free the city of Basra from the evil spell cast by a wizard, which his journey takes him to mysterious islands and he must battle magical creatures in order to save the world.

Television[edit]

English language series and films[edit]

- Sinbad Jr. and his Magic Belt (1965).

- The Freedom Force (TV Series) (1978).

- The Adventures of Sinbad (1979) – TV animated film.

- Mystery Science Theater 3000 (1993) episode: The Magic Voyage of Sinbad

- The Fantastic Voyages of Sinbad the Sailor (1996–1998) is an American animated television series based on the Arabian Nights story of Sinbad the Sailor and produced by Fred Wolf Films that aired beginning 2 February 1998 on Cartoon Network.[23]

- The Adventures of Sinbad (1996–98) is a Canadian Action/Adventure Fantasy television series following on the story from the pilot of the same name.

- The Backyardigans (2007) episode: "Sinbad Sails Alone".

- Sinbad (2012) – A UK television series from Sky1.

- Sindbad & The 7 Galaxies (2016 by Sun TV, picked up by Toonavision in 2020) is an animated children's comedy adventure TV series[24] created by Raja Masilamani and IP owned by Creative Media Partners.[25]

Note: Sinbad was mentioned, but did not actually appear, in the Season 3 episode Been There, Done That of Xena Warrior Princess when one of the story's lovers tells Xena that he was hoping that Hercules would have appeared to save his village from its curse.

Non-English language series and films[edit]

- Arabian Nights: Sinbad's Adventures (Arabian Naitsu: Shinbaddo No Bôken, 1975).

- Manga Sekai Mukashi Banashi: The Arabian Nights: Adventures of Sinbad the Sailor (1976) Japanese anime TV series, Directed by Sadao Nozaki and Tatsuya Matano. Producer Yuji Tanno. The origins of this is a series called Manga Hajimete Monogatari This is dubbed in English and narrated by Telly Savalas.

- Alif Laila (1993–1997), an Indian television series based on the One Thousand and One Nights which aired on Doordarshan's DD National. Episodes titled "Sindbad Jahaazi" focus on the adventures of the sailor, where he is portrayed by Shahnawaz Pradhan.[26]

- Princess Dollie Aur Uska Magic Bag (2004–2006), an Indian teen fantasy adventure television series on Star Plus where Vaquar Shaikh portrays Sinbad, one of the main characters in the show along with Ali Baba and Hatim.

- Magi: The Labyrinth of Magic (2012), Magi: The Kingdom of Magic (2013) and Magi: Adventure of Sinbad (2016) are Japanese fantasy adventure manga series.

- Janbaaz Sindbad (2015–2016), an Indian adventure-fantasy television series based on Sinbad the Sailor which aired on Zee TV, starring Harsh Rajput in the titular role.

Note: A pair of foreign films that had nothing to do with the Sinbad character were released in North America, with the hero being referred to as "Sinbad" in the dubbed soundtrack. The 1952 Russian film Sadko (based on Rimsky-Korsakov's opera Sadko) was overdubbed and released in English in 1962 as The Magic Voyage of Sinbad, while the 1963 Japanese film Dai tozoku (whose main character was a heroic pirate named Sukezaemon) was overdubbed and released in English in 1965 as The Lost World of Sinbad.[citation needed]

Video games[edit]

- In the Arabian Nights-themed video game Sonic and the Secret Rings, Sinbad looks almost exactly like Knuckles the Echidna.

- In 1978 Gottlieb manufacturing released a pinball machine named Sinbad,[27] the artwork featured characters from the movie Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger. Also released, in a shorter run, was an Eye of the Tiger pinball game.[28]

- in 1996 the pinball game Tales of the Arabian Nights was released featuring Sinbad.[29] This game (manufactured by Williams Electronics) features Sinbad's battle with the Rocs and the Cyclops as side quests to obtain jewels. The game was adapted into the video game compilation Pinball Hall of Fame: The Williams Collection in 2009.

- In 1984 game simply called Sinbad was released by Atlantis Software.[30]

- In 1986 game called Sinbad and the Golden Ship was released by Mastertronic Ltd.[31]

- Another 1986 game called The Legend of Sinbad was released by Superior Software.[32]

- in 1987 game called Sinbad and the Throne of the Falcon was released by Cinemaware.[33]

Music[edit]

- In Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's suite Scheherazade, the 1st, 2nd, and 4th movements focus on portions of the Sinbad story. Various components of the story have identifiable themes in the work, including rocs and the angry sea. In the climactic final movement, Sinbad's ship (6th voyage) is depicted as rushing rapidly toward cliffs and only the fortuitous discovery of the cavernous stream allows him to escape and make the passage to Serindib.

- The song "Sinbad the Sailor" in the soundtrack of the Indian film Rock On!! focuses on the story of Sinbad the Sailor in music form.

- Sinbad et la légende de Mizan (2013) A French stage musical. the musical comedy event in Lorraine. An original creation based on the history of Sinbad the Navy, heroes of 1001 nights. A quest to traverse the Orient, 30 artists on stage, mysteries, combats, music and enviable dances ... A new adventure for Sinbad, much more dangerous than all the others.

- Sinbad's adventures have appeared on various audio recordings as both readings and dramatizations, including Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves/Sinbad the Sailor (Riverside Records RLP 1451/Golden Wonderland GW 231, played by Denis Quilley), Sinbad the Sailor (Tale Spinners for Children on United Artists Records UAC 11020, played by Derek Hart), Sinbad the Sailor: A Tale from the Arabian Nights (Caedmon Records TC-1245/Fontana Records SFL 14105, read by Anthony Quayle), Sinbad the Sailor /The Adventures of Oliver Twist and Fagin (Columbia Masterworks ML 4072, read by Basil Rathbone), 1001 Nights: Sinbad the Sailor and Other Stories (Naxos Audio 8.555899, narrated by Bernard Cribbins) and The Arabian Nights (The Voyages of Sinbad the Sailor) (Disneyland Records STER-3988).

- "Nagisa no Sinbad" (渚のシンドバッド) was the 4th single released by Pink Lady, a popular Japanese duo in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The song has been covered by former idol group W and by the Japanese super group Morning Musume.

Literature[edit]

- In The Count of Monte Cristo, "Sinbad the Sailor" is but one of many pseudonyms used by Edmond Dantès.

- In his Ulysses, James Joyce uses "Sinbad the Sailor" as an alias for the character of W.B. Murphy and as an analogue to Odysseus. He also puns mercilessly on the name: Jinbad the Jailer, Tinbad the Tailor, Whinbad the Whaler, and so on.

- In Dylan Thomas' play for voices, Under Milk Wood, the barman of the Sailor's Arms pub is named Sinbad Sailors.

- Edgar Allan Poe wrote a tale called "The Thousand-and-Second Tale of Scheherazade". It depicts the 8th and final voyage of Sinbad the Sailor, along with the various mysteries Sinbad and his crew encounter; the anomalies are then described as footnotes to the story.

- Polish poet Bolesław Leśmian's Adventures of Sindbad the Sailor is a set of tales loosely based on the Arabian Nights.

- Hungarian writer Gyula Krúdy's Adventures of Sindbad is a set of short stories based on the Arabian Nights.

- In John Barth's "The Last Voyage of Somebody the Sailor", "Sinbad the Sailor" and his traditional travels frame a series of 'travels' by a 20th-century New Journalist known as 'Somebody the Sailor'.

- Pulitzer Prize winner Steven Millhauser has a story entitled "The Eighth Voyage of Sinbad" in his 1990 collection The Barnum Museum.

Comics[edit]

- "Sinbad the Sailor" (1920) artwork by Paul Klee (Swiss-German artist, 1879–1940).

- In 1950, St. John Publications published a one shot comic called Son of Sinbad.[34]

- In 1958, Dell Comics published a one shot comic based on the film The 7th Voyage of Sinbad.[35]

- In 1963, Gold Key Comics published a one shot comic based on the film Captain Sinbad.[36]

- In 1965, Dell Comics published a 3 issue series called Sinbad Jr.[37]

- in 1965 Gold Key Comics published a 2 issue mini-series called The Fantastic Voyages of Sinbad.[38]

- In 1974 Marvel Comics published a two issue series based on the film The Golden Voyage of Sinbad in Worlds Unknown #7[39] and #8.[40] They then published a one shot comic based on the film The 7th Voyage of Sinbad in 1975 with Marvel Spotlight #25.[41]

- In 1977, the British comic company General Book Distributors, published a one shot comic/magazine based on the film Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger.[42]

- In 1988, Catalan Communications published the one shot graphic novel The Last Voyage of Sinbad.[43]

- In 1989 Malibu Comics published a 4 issue mini-series called Sinbad,[44] and followed that up with another 4 issue mini-series called Sinbad Book II: In the House of God In 1991.[45]

- In 2001, Marvel Comics published a one shot comic that teamed Sinbad with the Fantastic Four called Fantastic 4th Voyage of Sinbad.[46]

- In 2007, Bluewater Comics published a 3 issue mini-series called Sinbad: Rogue of Mars.[47]

- In 2008, the Lerner Publishing Group published a graphic novel called Sinbad: Sailing into Peril.[48]

- In 2009, Zenescope Entertainment debuted Sinbad in their Grimm Fairy Tales universe having him appearing as a regular ongoing character. He first appeared in his own 14 issue series called 1001 Arabian Nights: The Adventures of Sinbad.[49] Afterwards he appeared in various issues of the Dream Eater saga,[50] as well as the 2011 Annual,[51] Giant-Size,[52] and Special Edition[53] one-shots.

- In 2012, a graphic novel called Sinbad: The Legacy, published by Campfire Books, was released.[54] He appears in the comic book series Fables written by Bill Willingham, and as the teenaged Alsind in the comic book series Arak, Son of Thunder—which takes place in the 9th century AD—written by Roy Thomas.

- In Alan Moore's The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Black Dossier, Sinbad appears as the Immortal Orlando's lover of thirty years, until he leaves for his 8th Voyage and never returns.

- In The Simpsons comic book series "Get Some Fancy Book Learnin'", Sinbad's adventures are parodied as "Sinbart the Sailor".

- "The Last Voyage of Sinbad" by Richard Corben and Jan Strnad originally appeared as "New Tales of the Arabian Nights" serialized in Heavy Metal magazine, issues #15–28 (1978–79) and was later collected and reprinted as a trade paperback book.

- Sinbad is a major character in the Japanese manga series Magi: The Labyrinth of Magic written and illustrated by Shinobu Ohtaka.

Theme parks[edit]

- Sinbad provides the theme for the dark ride Sinbad's Storybook Voyage at Tokyo DisneySea.

- Sinbad embarks on an adventure to save a trapped princess in the water-based boat ride, The Adventures of Sinbad at Lotte World in Seoul, South Korea.[55]

- The Efteling theme park at Kaatsheuvel in the Netherlands has a land themed after Sinbad called De Wereld van Sindbad (The World of Sinbad). It includes the indoor roller coaster Vogel Rok, themed after Sinbad's fifth voyage, and Sirocco, a teacups ride.

- The elaborate live-action stunt show The Eighth Voyage of Sinbad at the Universal Orlando Resort in Florida features a story inspired by Sinbad's voyages.

Other references[edit]

- Actor and comedian David Adkins has performed under the stage name Sinbad since the 1980s.

- An LTR retrotransposon from the genome of the human blood fluke, Schistosoma mansoni, is named after Sinbad.[56] It is customary for mobile genetic elements like retrotransposons to be named after mythical, historical, or literary travelers; for example, the well-known mobile genetic elements Gypsy and Mariner.

See also[edit]

- Aeneid

- Gulliver's Travels

- List of literary cycles

- Odyssey

- Sunpadh

- The Voyage of Bran

- Baron Munchausen

Notes[edit]

- ^ The theme of a snake swallowing an elephant, originating here, was taken up by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in The Little Prince.

References[edit]

- ^ Pinault 1998, pp. 721–722.

- ^ The new Arabian winter nights entertainments. Containing one thousand and eleven stories, told by the Sultaness of the Indies, to divert the Sultan from performing a bloody vow he had made to marry a virgin lady every day, and have her beheaded next morning, to avenge himself for the adultery committed by his first Sultaness. The whole containing a better account of the customs, manners, and religions of the Indians, Persians, Turks, Tartarians, Chineses, and other eastern nations, than is to be met with in any English author hitherto set forth. Faithfully translated into English from the Arabick manuscript of Haly Ulugh Shaschin., London: John de Lachieur, 1711.

- ^ The Adventures of Houran Banow, etc. (Taken from the Arabian Nights, being the third and fourth voyages of Sinbad the Sailor.), London: Thornhill and Sheppard, 1770.

- ^ The seven voyages of Sinbad the sailor. And The story of Aladdin; or, The wonderful lamp, Philadelphia: Philadelphia, 1794

- ^ Burton, Richard. "The Book of one thousand & one nights" (translation online). CA: Woll amshram. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Marzolph, Ulrich; van Leeuwen, Richard (2004), The Arabian nights encyclopedia, vol. 1, pp. 506–8.

- ^ Irwin, Robert (2004), The Arabian nights: a companion.

- ^ JPG image. stefanmart.de

- ^ JPG image. stefanmart.de

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. pp. 122–123. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (2009). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons (3rd ed.). New York: Checkmark Books. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-8160-6600-1.

- ^ "映画ドラえもんオフィシャルサイト_Film History_12". dora-movie.com. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "The Adventures of Sinbad". The Times of India.

- ^ Article on Arabian Nights at Turner Classic Movies accessed 10 January 2014

- ^ Swires, Steve (April 1989). "Nathan Juran: The Fantasy Voyages of Jerry the Giant Killer Part One". Starlog Magazine. No. 141. p. 61.

- ^ "Captain Sinbad (1963) - Byron Haskin | Synopsis, Characteristics, Moods, Themes and Related | AllMovie".

- ^ Dread Central – The Asylum Breeding a Mega Piranha

- ^ Sinbad and the Minotaur on IMDb

- ^ DVD review: Sinbad and the Minotaur

- ^ a b c d e Rajadhyaksha, Ashish; Willemen, Paul (1999). Encyclopaedia of Indian cinema. British Film Institute. ISBN 9780851706696. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ Roberto Poppi, Mario Pecorari (15 May 2024). Dizionario del cinema italiano. I film. Gremese Editore, 2007. ISBN 978-8884405036.

- ^ Paolo Mereghetti (15 May 2024). Il Mereghetti - Dizionario dei film. B.C. Dalai Editore, 2010. ISBN 978-8860736260.

- ^ Erickson, Hal (2005). Television Cartoon Shows: An Illustrated Encyclopedia, 1949 Through 2003 (2nd ed.). McFarland & Co. p. 322. ISBN 978-1-4766-6599-3.

- ^ Milligan, Mercedes (27 January 2016). "'Sindbad & The 7 Galaxies' Launches with Presales". Animation Magazine. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ Dickson, Jeremy (26 January 2019). "Creative Media Partners debuts Sindbad & the 7 Galaxies". KidScreen.

- ^ "Shahnawaz Pradhan who plays Hariz Saeed in 'Phantom' talks about the film's ban in Pakistan". dnaindia.com. 22 August 2015.

- ^ "Gottlieb 'Sinbad'". Internet Pinball Machine Database. IPDb. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Gottlieb 'Eye Of The Tiger'". Internet Pinball Machine Database. IPDb. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Internet Pinball Machine Database: Williams 'Tales of the Arabian Nights'". Ipdb.org. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Sinbad for ZX Spectrum (1984)". MobyGames. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Sinbad & the Golden Ship for ZX Spectrum (1986)". MobyGames. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Lemon – Commodore 64, C64 Games, Reviews & Music!". Lemon64.com. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Sinbad and the Throne of the Falcon – Amiga Game / Games – Download ADF, Review, Cheat, Walkthrough". Lemon Amiga. 23 August 2004. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Son of Sinbad". Comics. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "The 7th Voyage Of Sinbad Comic No. 944 – 1958 (Movie)". A Date In Time. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Captain Sinbad". Comics. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Sinbad Jr". Comics. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "The Fantastic Voyages of Sinbad". Comics. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Worlds Unknown No. 7". Comics. 24 August 2006. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Worlds Unknown No. 8". Comics. 24 August 2006. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Marvel Spotlight No. 25". Comics. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "The Comic Book Database". Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "The Last Voyage of Sinbad". Comics. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Sinbad". Comics. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "The Comic Book Database". Comic Book DB. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Fantastic 4th Voyage of Sinbad". Comics. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Sinbad: Rogue of Mars". Comics. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Comic vine, archived from the original (JPEG) on 12 November 2012.

- ^ "1001 Arabian Nights: The Adventures of Sinbad". Comics. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Grimm Fairy Tales: Dream Eater Saga". Comics. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ "Grimm Fairy Tales 2011 Annual". Comics. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ "Grimm Fairy Tales Giant-Size 2011". Comics. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ "Grimm Fairy Tales 2011 Special Edition". Comics. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ "Sinbad: Legend of the Seven Seas". Comic Corner. Camp fire graphic novels. 4 January 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ "Lotte World Attractions". The Adventures of Sinbad.

- ^ Copeland, Claudia S.; Mann, Victoria H.; Morales, Maria E.; Kalinna, Bernd H.; Brindley, Paul J. (23 February 2005). "The Sinbad retrotransposon from the genome of the human blood fluke, Schistosoma mansoni, and the distribution of related Pao-like elements". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 5 (1): 20. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-5-20. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 554778. PMID 15725362.

Sources[edit]

- Haddawy, Husain (1995). The Arabian Nights. Vol. 1. WW Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-31367-3.

- Pinault, D. (1998). "Sindbad". In Meisami, Julie Scott; Starkey, Paul (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Literature. Vol. 2. Taylor & Francis. pp. 721–723. ISBN 9780415185721.

Further reading[edit]

- Beazley, Charles Raymond (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 141–142. This includes a detailed analysis of potential sources and comparable tales across contemporaneous and earlier texts.

- Copeland, CS; Mann, VH; Morales, ME; Kalinna, BH; Brindley, PJ (23 February 2005). "The Sinbad retrotransposon from the genome of the human blood fluke, Schistosoma mansoni, and the distribution of related Pao-like elements". BMC Evol Biol. 5 (1): 20. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-5-20. PMC 554778. PMID 15725362.

- Favorov, OV; Ryder, D (12 March 2004). "Sinbad: a neocortical mechanism for discovering environmental variables and regularities hidden in sensory input". Biol Cybern. 90 (3): 191–202. doi:10.1007/s00422-004-0464-8. PMID 15052482. S2CID 680298.

- Marcelli, A; Burattini, E; Mencuccini, C; Calvani, P; Nucara, A; Lupi, S; Sanchez Del Rio, M (1 May 1998). "Sinbad, a brilliant IR source from the DAPhiNE storage ring". Journal of Synchrotron Radiation. 5 (3). J Synchrotron Radiat: 575–7. Bibcode:1998JSynR...5..575M. doi:10.1107/S0909049598000661. PMID 15263583..

External links[edit]

- Mart, Stefan, Story of Sindbad the Sailor.

- Mart, Stefan (1933), "Sindbad the Sailor: 21 Illustrations by Stefan Mart", Tales of the Nations (illustrations)

- Adventure film characters

- Basra

- Fictional Muslims

- Fictional businesspeople

- Fictional Iraqi people

- Fictional people from Baghdad

- Fictional sailors

- Fiction set in the 8th century

- Fiction set in the 9th century

- Iraqi folklore

- Male characters in fairy tales

- Male characters in literature

- Maritime folklore

- Medieval Arabic literature

- Medieval legends

- One Thousand and One Nights characters

- People whose existence is disputed

- Roc (mythology)

- Sinbad the Sailor

- Adventure characters