The photograph above was taken from an airplane, circling a small collection of grass huts in the middle of the Amazon. These are people who have likely never seen an airplane -- or anyone outside their tribe. This story deals with "contact" and the many ethical and safety issues that make this topic so controversial. I cannot help but imagine the same photo where, instead of naked tribesmen, a group of Americans or Englishmen are being scrutinized (and perhaps terrorized) by occupants of an alien craft. The consequences of contact with a higher technological culture are perhaps equally ominous and lethal. We have been taught to seek solutions to our social and environmental problems through technology. Indeed, technology does make it possible for 6.7 billion humans to exist. But isn't it kind of special to know that somewhere, somehow, people live productive and happy lives without any technology at all? How is that possible? What determines happiness then? Sadly, we may never know. Every time we encounter a group expressing their own evolved set of cultural options -- who have different visions of life and meaning -- we destroy their culture and awkwardly assimilate them as a lower class in our own. Here are some recent stories of uncontacted tribes in Latin America. --Editor In Paraguay a Familiar Story is Playing Out Saturday 17 September 2011 by: Sean O'Leary, Council on Hemispheric Affairs | Report In Paraguay, the Ayoreo people are fighting for their very survival. These indigenous people are struggling to save their ancestral home in the Chaco region from cattle companies, farmers and religious sects who are moving into the region and clearing the land. New arrivals do this to make the land suitable for farming and grazing cattle. The combination of burning and then bulldozing the land leaves the region barren. The Chaco region in southwestern Paraguay is one of the most inhospitable lands in South America; while it composes 60 percent of the country's area, it is inhabited by only two percent of the Paraguayan population. Popular filmmaker and conservationist David Attenborough has praised the beauty of Chaco calling it "one of the last great wilderness areas left in the world" and called for its protection due to the many plants and animals that inhabit its dense forests. [below]

The preservation of forested areas is not only vital to sustaining the region's biodiversity; the survival of the Ayoreo people also depends upon it. It is not simply a matter of the Ayoreo people moving somewhere else. The territory called Eami in their language, is tied to their history and very identity and thus valued as sacred. As one of the members of the Ayoreo point out, "Our history is etched in every stream, in every waterhole, on the trees ... our territory expresses itself through our history because the Ayoreo people and our territory are a single being." Big Beef

Although many Paraguayan officials support expanding the cattle and farming industries throughout the Chaco as a means to boost the economy, the long-term damage to the nation from both a human rights and an environmental perspective would be catastrophic. The practice of slash and burn agriculture will only bring short-term benefits at the expense of Paraguay's ecology and the destruction of the Ayoreo people.

One of the last uncontacted groups in the world The Ayoreo-Totobeigosode, a sub community of the Ayoreo, is one of the last uncontacted groups in the world, Brazilian beef corporations, wealthy farmers, and Mennonite communities seeking remote areas in which to live a life based on a literal translation of the bible are encroaching on the Ayoreo lands. In the 1950s, the Ayoreo people lived in an area 2,800,000 hectares; now they claim only 550,00 hectares -- a loss of nearly 80 percent. According to the BBC, over 1 million hectares have disappeared since 2007. Moreover, the new arrivals into the Chaco region have brought diseases, such as measles that were previously unknown to the Ayoreo people.

Both BBC S.A and River Plare S.A have been caught twice by satellite imagery of illegally clearing protected forestry in Chaco. Yaguarete Pera, another Brazilian cattle corporation in the region was found guilty of deforesting the region and concealing evidence of the displace Ayoreo's former presence. No stranger to controversy, Survival International awarded Yaguarete Pera their 2010 "Greenwashing Award" for "dressing up the wholesale destruction of a huge area of the Indians' forest as a noble gesture for conservation." Survival International issued a report to the United Nations' Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) on 10th August, 2011 stating that the Ayores-Totobeigosode face the "imminent danger" of extermination. Promises of "the good life" There are only 5,600 Ayoreo Indians left today with about 3,000 living in Bolivia and 2,600 in Paraguay. The Ayoreo people were lured out of their homes and into modern society with promises of a better life; many were dragged out forcibly. As Aquino Picanerai, a member of the Ayoreo recalled, "They brought us to the world of the white people and locked us up in this concentration camp."

Certain government officials in Paraguay have expressed the need for investment and claim that the human rights and deforestation situation has been exaggerated. Paraguay's weak laws facilitate the wholesale destruction of the forest. Under current Paraguayan laws an individual or corporation is allowed to clear forest on up to 75% of its land. They may then sell the remaining 25 % to another entity who is entitled to clear 75% of that plot. The process leads to the complete destruction of that land. Last year, Paraguay's congress failed to pass a law that would have placed a ban on deforestation in the Chaco region. In an attempt to explain public silence on injustices being perpetrated in the Chaco region, Benno Glauser, the Director of Iniciativa Amotocodie explains "public opinion has no opinion on the matter." The Chaco is at the periphery of a country of little international importance. Even in Paraguay, the Chaco does not embody the homogenous Guaraní society composing the majority of the population -- more than 98 percent of Paraguayans are either mestizo or of primarily European descent. In contrast, the wilderness of the Chaco is sparsely populated by indigenous tribes and religious isolationists. In the public discourse, the cause to save the Ayoreo remains an obscure impediment to economic development. If this matter continues to fall on deaf ears then the allure of profits at the expense of humanity will prevail.

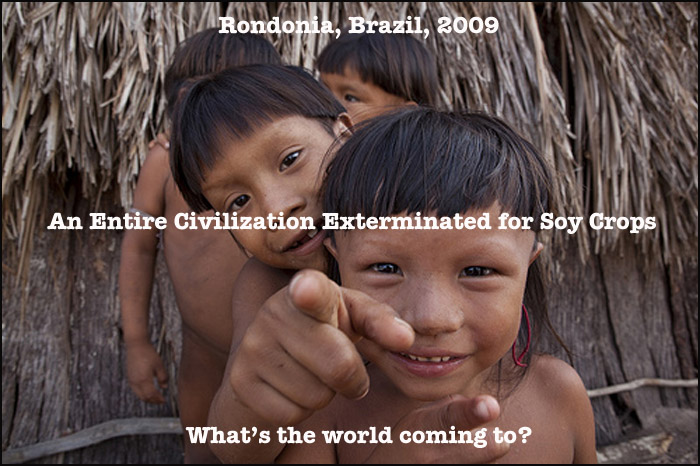

A Sad Look at Humanity in the 21st Century Most American families will celebrate the holidays with certain traditions. We'll gather together and have a special meal, perhaps sing some songs and we'll hear about who is doing what. We will also think about those members of our family that have passed away. There will be some crying, but mostly it will be a fun time. It's important to remind ourselves how miraculous it is to have a family. In the genetic sense, it means that an unbroken lineage has extended back through many generations -- surviving such things as wars, diseases, famines and accidents. If you really think about it, our families go back hundreds of thousands of years. That's how far back we can all trace our genetic lineage to the "mitochondrial Eve," the first homo sapiens. Now think of how horrible it would be if something were to wipe out an entire family. How terrible it would be to have that long lineage of thousands of generations to abruptly end because of something relatively insignificant. Meet The Akuntsu Five The picture below is of a family -- a tribal family in the remote jungle of Western Brazil. Look at them. They are gathered together to celebrate their holiday. But they don't have much to be happy about. They are the last five survivors of their tribe and they will soon become extinct.

At the time this picture [above] was taken there were just five remaining survivors from an original group of about 7,000. They called themselves the Askuntsu and they made their home in a remote part of the Brazilian Amazon call Rondonia. For thousands of years the Askuntsu have enjoyed a simple life in this garden and no contact with the outside world. They wore no clothes and did not know the meaning of shame. They respected their environment and revered its ability to feed and protect them while they went about raising their families doing their daily chores of hunting, gardening and preparing food. It was a kind of Edenic life, free from want and largely based in the present tense. But that ended about a decade ago. Corporate Greed, Again The "outside world" lives for the future. It has many wants and needs. It has also lost contact with the natural forces that regulate growth and maintain a balance between the resources and the environment. The outside world chooses to live in crowded cities and uses money to buy what it wants. And it wants beef. Bending to the demands of their rapidly growing population, Brazil opened up the remote Amazon land to huge agricultural and mining corporations. With some government help, these corporations first carved railways through the dense jungles. These were followed by a major highway, BR-364, which allowed heavy equipment and trucks to penetrate the dense jungle. Next the unemployed city dwellers quickly followed with their dreams of easy money and good wages. Rondonia is one of the last frontiers, being on Brazil's far west border with Bolivia. And it's also the last unexplored wilderness where indigenous tribes, like the Akuntsu, were peacefully living and thriving in their timeless co-existence with nature.  Before our "outside world" penetrated to Rondonia, we had encountered other isolated tribes in the world. The Europeans encountered tribes when they colonized Africa. Then there were the Indians who were already inconveniently living in the North American continent that was supposedly "discovered" by more Europeans. Sadly, these encounters didn't turn out very well for the indigenous people. Within a few years of their encounter with the pilgrims, over 90 percent of American Indian tribes were wiped off the North American continent. These acts of genocide are condemned by everyone. The Brazilian government knows that genocide is wrong. After the first encounters with Amazon tribes they established laws to protect them. A special bureau of Indian Affairs (FUNAI) was established. When a tribe was encountered, they would set up a preserve where any impact on their environment would be prohibited or severely limited. At least that's how it was proposed. But, as he Akintsu learned, the devil is in the details. As the ambitious workers flooded into Rondonia's lush jungle, they cut and burned the trees, exposing the thin layer of soil to the elements. They planted soy beans to feed cattle and quench the "outside world's" taste for beef. As the fragile land lost its fertility, they used fertilizers and pesticides to extend their viability -- inevitably giving up the exhausted land and moving deeper into the jungle, where the process of defoliating would continue again... and again. Satellite images clearly show the devastation as lush green patches of virgin jungle are scarred by raw earth in clearly defined rectangles. It's like a cancer eating away all plant and animal life. These scars will remain as the valuable topsoil has forever been depleted. It didn't take long for small towns to appear in Rondonia. Then larger towns, like Corumbaria, developed along with the agricultural economy. People started building houses, schools and churches. Soon their were governments, politicians and police. Their lifeblood was the agricultural development; they all knew that. Then it happened. This Is "The End" The Akuntsu tribe numbered 7,000 people. We can only guess what they thought when they heard the chainsaws and bulldozers cutting down their jungle. Who were these people with these loud machines? Why were they destroying the land? Representatives from FUNAI encountered a small group of Indians in the south-east corner of Rondonia in 1995. By then the large agricultural and cattle ranching farms had been well established. These Indians kept telling stories of a large tribe that lived nearby, but the FUNAI workers never encountered them. Then, upon investigating traces of old huts, gardens, meeting houses and pottery, they found the tribe -- massacred. By the time the "outside world" spotted the Akuntsu it was too late -- too late to stop cutting the trees, too late to stop the expanding soy farms -- and especially too late to inform the Brazilian government that an uncontacted civilization existed. It was inconvenient for everyone and so the Akuntsu were simply exterminated -- all but six people that is. Rumors in the Corumbiara region told of the massacre of uncontacted Indians at the hands of gunmen employed by cattle ranchers. FUNAI found evidence of the massacre -- an entire Indian maloca had been bulldozed and covered with earth by ranchers in an attempt to hide the attack.  The oldest member, Ururu [above], was among the six survivors of a massacre that killed thousands of men, women and children in their homeland of Omere, in the state of Rondia. The world has done little to prosecute those who committed this act. Sadly, Ururu passed away in her sleep in 2009. Now there are only five. The other side of the story I know there are two sides to every story, so I contacted sources in Rondonia to get the other side. I was shown pictures of school children, holding up signs that read "Peace" and I was told by residents that they were ashamed about what happened. I was even told that it would and could never happen again. But then, on December 9th, 2009 I learned of more mysery. I was sent an anonymous e-mail with a link to a story. Two "peasants" who were supporting the rights of some remaining indigenous tribes in the region were murdered. Their bodies were discovered with signs that they had been tortured before death. Their fingernails had been pulled out and their skin had been cut off. This was clearly meant to be a warning against any further support for the existing local tribes. The report stated that the local police were investigating and that a security group, assigned to guard the agricultural developments, were the main suspects. These is the same group responsible for the massacre of the Akuntsu. Justified anger... and frustration

Does this anger you? Just look at one of the survivors of this genocide [above]. Her name is Inutela. She's posing for a photograph taken by a photographer named Fiona Watson, who works for Survival International. She's wearing a necklace that was made from collected pieces of plastic pesticide containers. She doesn't understand that they are poisonous. She doesn't understand anything that has happened. Why was her family -- even small children -- all killed? Why are people destroying the wonderful jungle and making the land die? What could possibly be worth so much to make this happen? Although their land has been legally recognised and FUNAI maintains a permanent presence in the area, the Akuntsu are still surrounded by hostile ranchers. Some still have buildings, employees and herds of cattle in the Akuntsu territory. FUNAI is trying to expel the ranchers, and the case is now in the courts. Could it get even worse? In December 2009, gunmen -- believed to be these same ranchers -- launched an attack on the last survivor of an uncontacted Amazon tribe in a remote part of Brazil's rainforest. That's right. He's the LAST survivor of his entire tribe. The tribesman, known as the "man of the hole" because of the pits he digs for trapping animals and because he stays in hiding, is believed to have survived the attack. The incident took place in Tanaru, an indigenous territory of Rondonia. Ranchers who oppose government efforts to protect the man's land were the likeliest perpetrators, said the Survival International group's director, Stephen Corry. "His tribe has been massacred and now the 'man of the hole' faces the same fate. The ranchers must allow this man to live out his last days in peace on his own land, and the authorities must do all they can to protect it."How inconvenient for the ranchers. As long as he stays alive they cannot take his land, burn all the foliage and use the soil for a couple of harvests of soy -- then move on leaving behind a sterile patch of dirt. Officials from FUNAI discovered its protection post was ransacked and found empty shotgun cartridges nearby in the forest. "This is a serious situation. The Indian's life is being put in danger by the interests of the ranchers," said Altair Algayer, a FUNAI official. Police have investigated the incident but, of course, nobody has been charged. The man's age and name is unknown, but he is believed to be the sole survivor of a tribe massacred by ranchers in the 1970s and 1980s. He traps animals by digging holes lined with spikes and, in the center of his hut, he has dug a hole in which he hides when outsiders approach. The site is surrounded by cattle ranches and soy plantations. It won't be long before he is gone. The "outside world" needs beef.

Fleeting images of the man [above] were captured by the filmmaker Vincent Carelli in his film ‚ Corumbiara, which documents the plight of the Akuntsu and other tribes in the region.

Contact Means Death

Above: The Ingá Stone, a possibly pre-Columbian set of petroglyphs found in Paraíba State, Brazil. It's one of several pieces of evidence that the Amazon once held civilizations which were wiped out by disease after contact with Europe.[1]

"We easily believe that a band of hostile Indians confronting an airplane from a clearing do so out of ignorance and fear. But the likely truth is harder to face: The tribe might have threatened the observers precisely because they had encountered some of the worst aspects of our culture before, and suffered grievously. These images of a people courageously standing against us are not symbols of their ignorance, but of ours." --Neuroanthropology [2]

Notes:

[1] Public Domain image by Jp. Juarez, from Wikimedia Commons.

[2] http://blogs.plos.org/neuroanthropology/2011/02/09/%E2%80%98the-last-free-people-on-the-planet%E2%80%99/

COMMENTS:

|

While the Ayoreo people were legally awarded some disputed land by the Paraguayan government, two Brazilian beef corporations, BBC S.A and River Plate S.A are refusing to hand over the land until they are sufficiently compensated. These companies are seeking permission to clear a large area of land bordering on the Ayoreo's. This will mean fencing the Ayoreos in to a smaller area, marginalizing them even further.

While the Ayoreo people were legally awarded some disputed land by the Paraguayan government, two Brazilian beef corporations, BBC S.A and River Plate S.A are refusing to hand over the land until they are sufficiently compensated. These companies are seeking permission to clear a large area of land bordering on the Ayoreo's. This will mean fencing the Ayoreos in to a smaller area, marginalizing them even further.

Lacking the necessary skills to thrive in modern society and disenchanted with their situation, these indigenous people have since returned to their more traditional way of life. Others rejected modernity from the start, opting never to leave the forest, hoping to remain hidden and unmolested from the outside world. Sadly this will not be the case. Rising beef profits and the availability of cheap land continues to bring speculators seeking fortunes into the region.

Lacking the necessary skills to thrive in modern society and disenchanted with their situation, these indigenous people have since returned to their more traditional way of life. Others rejected modernity from the start, opting never to leave the forest, hoping to remain hidden and unmolested from the outside world. Sadly this will not be the case. Rising beef profits and the availability of cheap land continues to bring speculators seeking fortunes into the region.