(CNN) -- It's a discovery that could rewrite the story of southeastern United States. Stone tools and mastodon bones found at the bottom of a Florida river point to humans living in the region 14,550 years ago. That's more than 1,500 years earlier than previously believed, scientists say.

"This is a big deal," said Jessi Halligan, one of the study's authors and an assistant professor of anthropology at Florida State University.

"It's pretty exciting. We thought we knew the answers to how and when we got here, but now the story is changing." The discovery on the Aucilla River was reported Friday by the journal Science Advances. Here are some of the details:

Butchered bones, knives

The four-year study included sending divers to the Page-Ladson site, a deep hole 30 feet underwater in the Aucilla River, researchers said. There, divers excavated artifacts such as butchered bones of extinct animals, a mastodon tusk and a biface, which is a knife fragment with sharp edges.

Divers excavated bones and tools from the Page-Ladson, which is 30 feet underwater in the Aucilla River. "At Page-Ladson, hunter-gatherers, possibly accompanied by dogs, butchered or scavenged a mastodon carcass at the sinkhole's edge next to a small pond at around 14,550 years ago," the authors said in Science Advances.

What was once a pond was buried beneath the murky waters for a series of reasons, including centuries of civilization, rising sea levels and layers of sediment. "These people had successfully adapted to their environment; they knew where to find freshwater, game, plants, raw materials for making tools, and other critical resources for survival." The scientists used radiocarbon dating techniques to find out how old the artifacts are.

Aaaah! What about the Clovis?

Until that point, researchers had believed the Clovis people were among the first inhabitants of the Americas about 13,000 years ago, according to the study. Page-Ladson is the first pre-Clovis site documented in the southeastern part of North America, it said. "The new discoveries at Page-Ladson show that people were living in the Gulf Coast area much earlier than believed," said Michael R. Waters, director of Texas A&M's center for the study of the first Americans. Waters was one of the study's lead authors.

In the 1980s, other researchers had retrieved several stone tools and a mastodon tusk from the site, but their discovery did not make much news. Halligan and her colleagues returned to the site in 2012 and expanded on the previous research and archaeological finds. In one of the instances, a mastodon tusk recovered earlier had deep grooves. They concluded the grooves were made by humans during the tusk's extraction.

Now... more discoveries that have been suppressed because of politicizing the "Native Americans came from Asia" theory. Enter -- the European SOLUTREANS!

Scallop fishermen net historic artifacts

Tasty deep-sea scallops like to burrow deep in the ocean floor. Fishermen plow and trawl the sea bottom far off shore, pulling up thousands of scallops at a time in their nets. Sometimes they also find other things.

In 1971 a scallop boat, the Cinmar, was fishing 60 miles east of the Virginia cape, in 240 feet of water when they pulled up part of the jaw from an ancient mastodon -- a large extinct elephant from the last ice age. Along with this catch they also found a curious stone spear point that resembled the famous Clovis points from 13,000 years ago.

In 1971 a scallop boat, the Cinmar, was fishing 60 miles east of the Virginia cape, in 240 feet of water when they pulled up part of the jaw from an ancient mastodon -- a large extinct elephant from the last ice age. Along with this catch they also found a curious stone spear point that resembled the famous Clovis points from 13,000 years ago.

The area where these artefacts were found was once dry land. During the last ice age the oceans of the world were much lower. Much of their water was locked up in huge glaciers that covered the Northern latitudes. The bones and spear were likely remnants of pre-historic hunting by some of the earliest inhabitants of North America. But there were even more surprises to come.

Carbon dating of the mastodon bone indicated it was 22,760 years old. Researchers also scrutinized the blade. It had not been smoothed by wave action or tumbling. They concluded the blade had not been pushed out to sea but had been buried where the Cinmar found it.

"My guess is the blade was used to butcher the mastodon... I'm almost positive... Its makers probably paddled from Europe and arrived in America thousands of years ahead of the western migration, making them the first Americans."

Dennis J. Stanford, co-author of Across Atlantic Ice: The Origin of America's Clovis Culture and Smithsonian Institution anthropoligist.

Chemical analysis of the spear point showed that it originated from flint in an area that is now France! Analysis of the way it was made showed that it was not a Clovis point at all, but a hand crafted point made by European humans known as the Solutreans.

The first humans entered North America from Western Europe -- not Asia

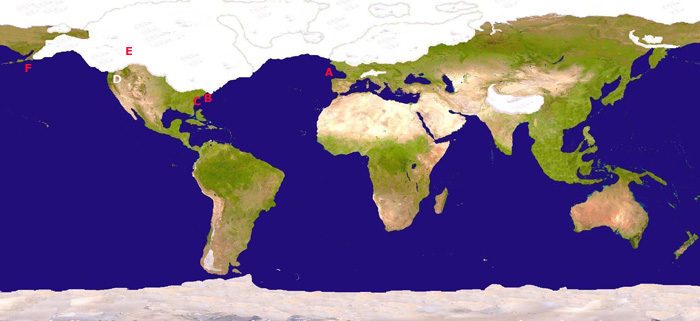

[Above:] The coastline of the continents was very different at the height of the last ice age. It was then that mysterious Stone Age European people known as the Solutreans paddled along an ice cap jutting into the North Atlantic. They lived like Inuits, harvesting seals and seabirds.

Most archaeological evidence of the Solutreans indicates they originated in what is now Spain, Portugal and southern France [A] beginning about 25,000 years ago. No skeletons have been found, so no DNA is available to study.

The Solutreans had a distinctive way of making their stone blades and this same skill and technology has been found in numerous archaeological sites along the East coast of North America [B and C].

Stone tools recovered from two other mid-Atlantic sites -- Cactus Hills, Va., 45 miles south of Richmond, and Meadowcroft Rockshelter, in southern Pennsylvania -- date to at least 16,000 years ago. Those tools also strongly resemble Solutrean blades found in Europe.

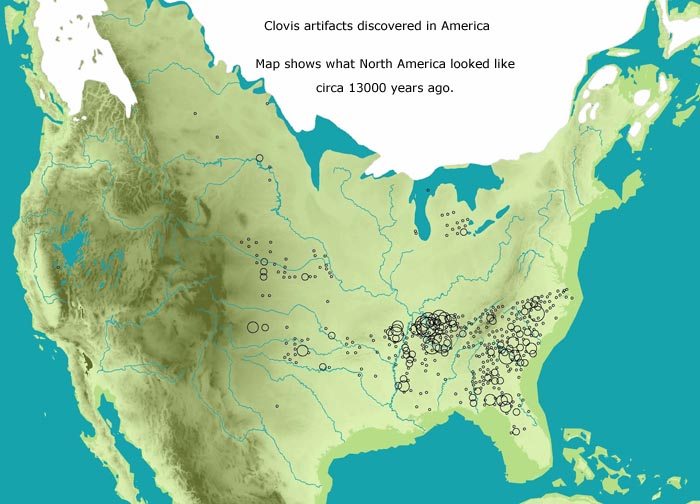

The Solutreans eventually spread across North America, carrying their distinctive blades with them and giving birth to the later Clovis culture, which emerged some 13,000 years ago. Clovis gets its name from Clovis, New Mexico, where the first such blade was discovered.

Old Paradigms Die Slowly

Until very recently the dominant theory of human migration to North America had Asians crossing the Bering Straits [F] to Alaska and coming through a narrow ice free corridor [E] that allowed access to the Central Plains. This was supposed to have happened around 15,000 years ago. A major archaeological site used to support the Asian "first" migration was the Dyuktai culture in Ushki, Siberia; however this site has recently been re-dated to a much younger 10,000 years old. Despite the much older dates of the Solutreans in eastern North America, many anthropologists continue to cling to the Beringia idea.

It is inevitable that these old ideas will give way to the Solutrean hypothesis. I'll give some of the reasons in this article, including some new discoveries in Nevada [D] and also:

- Evidence of knapping (stone tool making) techniques

- Evidence of DNA markers

- Evidence of ice flow data

- Evidence of cultural data

I think you will see that it is time to rewrite history and give credit to the Solutreans, not only for the Clovis Culture, but for the paleo-Indians of North America.

Evidence of stone tool techniques

Despite the best efforts of archaeologists and other researchers, the Siberian archaeological record has yet to yield compelling evidence to link the first American settlers with Siberia. One of the ways to establish such a link would be to find evidence in Siberia of the Clovis points that are found at most early American sites.

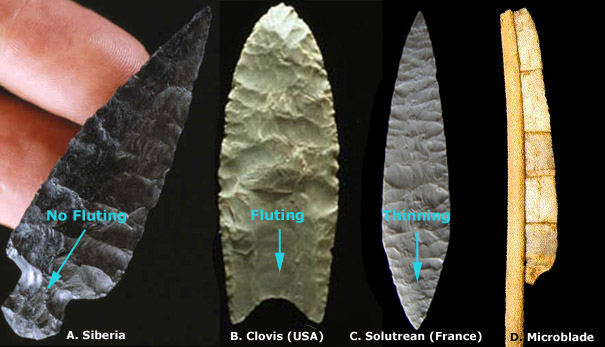

Excavation at the Dyuktai Cave site in north eastern Siberia revealed an assemblage that included stone spear points similar to Clovis points [A], as well as small stone tools known as microblades [D], and the remains of large mammoth and musk-ox. A series of similar sites were later found in the region, and some archaeologists have suggested that it was the people of the Dyuktai culture who crossed the Bering Land Bridge and settled the Americas.

Another difference in Asian v. European blades in that both Solutrean and Clovis are bi-facial, meaning that each side was completely flaked. In Asian blades the flute (i.e. a flaked or thinned zone at the base to accommodate fastening to a shaft) is absent and usually flaked more on one side than the other. Although the flute is dramatic on Clovis points, Solutrean points have a more subtle thinning at the base.

Although both the Dyuktai and Clovis sites exhibit evidence of big-game hunting, there are significant differences between them. For example, the Dyuktai points do not display the characteristic Clovis "flute" [B] . In addition, the microblade tools (i.e. several sharp pieces of stone were placed in grooved bone) which are common at the Dyuktai sites are not found at early archaeological sites in the Americas. Also, as we stated earlier, the Dyuktai site is much younger than Clovis.

Like cutting diamonds

Stone tools may seem primitive in today's world but, before the invention of metallurgy and electricity, these artifacts were the hi-tech of their time. Using these sharp instruments for hunting and cutting was vital to human survival. The designs had to evolve to be reliable and highly efficient. Once a particular design or production technique was perfected it was duplicated by the artisans and tool makers of that particular culture.

Archaeologists and anthropologists have spent years examining the stone knives and spear points of various ancient cultures. They have looked at every detail -- every step -- involved in shaping a rough stone to a streamlined spear point. Many, like Dennis Stanford and Bruce Bradley [1], have even attempted to duplicate the production of stone points from sites around the globe.

Finding the right type of stone is critical. Flint, quartz and jasper were prized for their strength and flaking abilities. Various techniques were used to remove flakes and shape the stones. Sometimes the stone was struck with another stone and other times the technique called for a softer implement such as an antler bone and just the right pressure to carefully crack and remove flakes from the surface or edge of a stone point.

"'Clovis' is the name given to the distinctive tools made by people starting around 13,000 years ago. The Clovis people invented the 'Clovis point', a spear-shaped weapon made of stone that is found in Texas and the rest of the United States and northern Mexico. These weapons were used to hunt animals, including mammoths and mastodons, from 13,000 to 12,700 years ago.

--Michael Waters, director of the Center for the Study of the First Americans in the Department of Anthropology at Texas A&M [source]

By understanding the various techniques used by different cultures they determined that the Clovis and older Solutreans had developed something special -- called "over flaking" -- where a large flake was removed laterally across the point instead of many smaller flakes. This was a dangerous technique if not done with a high degree of skill. One wrong move, or too much pressure, and the knife or spear point would be ruined.

It is this skill that they saw exhibited by the Solutreans, and later the Clovis culture, that convinced them of an ancestral link. No such technique appears in stone points from Siberia.

Once you make the connection between Clovis artifacts and the Solutreans, the distribution of Clovis in the East makes perfect sense. The origin of earliest inhabitants of North america did not come from the Northwest -- they came from Europe by way of the North Atlantic ice sheet and moved West across the continent.

The map [above] also suggests that they preferred to live near rivers, perhaps the preferential habitation of game. The map also suggests that the Clovis migration took them North through the ice-free corridor, although only a few artifacts have been found there.

Some die-hard archaeologists have denied the eastern origins of Clovis, claiming that they originated in the West, migrated South to Central America where they crossed over to the East coast and moved North. This complicated migration is used to explain the multitude of Clovis artifacts found in the East. Their evidence for this is a recent find of Clovis points in Alaska. But critics point out that the dates of these points are about 12,000 years ago -- well after the arrival of Clovis in the western continent. [source]

It is important to remember that the proponents of the Clovis/Solutrean hypothesis do not deny that a prior substantial migration to the Americas from Asia took place. It is possible that the continent was inhabited by humans tens of thousands of years before either group was in North America. What we are discussing here is the migration of a culture with historic traits such as tool making, hunting patterns and presumably a common language and social organization. We can only discover this kind of unique population if consistent evidence of these cultural traits is found.

Most certainly, migrations from Asia did eventually overcome those of the Solutreans and subsequent Clovis culture. Stone tool development changed as mastodons were replaced by smaller game. Rival tribes may have annihilated each other, as we have seen such violence in the Kennewick Man's remains. [source]

Intentionally buried time capsules

Most of the finds involving caches of Clovis artifacts were intentionally buried with the blades carefully stacked together and placed in a vertical alignment to avoid being crushed. The reason for these burials is unclear but may have been for safe keeping and re-use by hunters when their supply of blades or the stones to make them became scarce.

Also, archaeologists have found giant Clovis blades that are too big for hunting and appear more ornamental than utilitarian. Were these enlarged teaching tools to help future artisans? Or perhaps they had some religious or totem significance? We just do not know.

Besides stone blades, hooks and sewing needles made from bone have been found at some sites. It is thought that the Solutreans and later Clovis cultures must have been adept at making warm and durable clothing from animal skins to survive the cold climates.

This introduces another interesting hypothesis. The Inuit in alaska make sea worthy boats from animal skins. It is certainly possible that the Solutreans, having mastered the sewing of animal skins, could have done the same thousands of years earlier.

NEXT -- DNA Evidence linking American Indians to Europeans

Notes:

[1] Dennis J. Stanford and Bruce A. Bradley, ACROSS ATLANTIC ICE: The Origin of America's Clovis Culture, University of California Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-520-22783-5 (available from amazon.com)

Little did Domingo "Buzzy" Ybargoitia know that by drilling a well to bring water to his sheep, he would change the way we view the history of humans in the New World.

"My girls need to drink, that's all I was thinking about. It gets mighty dry around here come late summer anymore. I don't know what's going on, but I do know my granpoppa never had any trouble keeping his flock watered, and my pop didn't either. But I've had to truck it in from Marsing when it gets really hot."

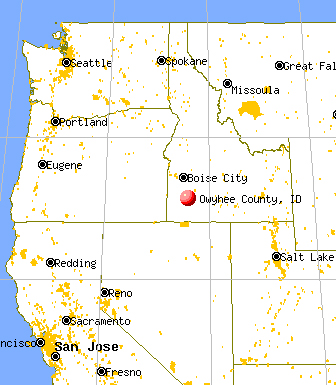

Ybargoitia manages his family's sheep operation in Idaho's lonely Owyhee Mountains, an hour's drive over rough roads from the tiny Oregon village of Jordan Valley. Two years ago this coming April, he brought a drilling contractor from Nampa to install a dependable well. It was tough drilling until they got through the dense lime deposits, or caliche, that underlies so much of this remote southwest corner of Idaho.

"A couple of times, I was afraid those boys were going to give up," says Ybargoitia. "They'd pull their bit out of the shaft and just shake their heads when they saw how chunked up it was getting."

On the second morning of drilling, they unearthed an astonishing surprise. The hole was below the caliche, down to about 26 feet, when Ted Burquart of the drill crew pulled what looked to be a child's doll from the mud and sand accumulating next to the hole.

"At first, I just thought it was just one of those Troll dolls you see hanging from rearview mirrors," explained Burquart. "I wiped the crud off and took a better look at it. It was whittled out of rock, I could tell that much. And what I thought was crazy Troll hair all flattened out was really a funny little cap. Like a beret, maybe."

Ybargoitia knew immediately what it was. As a youth, he had spent too many years with the Oinkari folk dancers of Boise to not recognize a traditional Basque txapela, even if it was small enough to top a five-inch figure. He stopped the drilling and sifted through the pilings with his fingers, wondering what else might have been brought up. Within minutes, he had found several blades, chipped to a razor's edge on both sides, ranging from 9 to 20 centimeters long. Each one had a notch into which a spear shaft could be set. He also found a small, partially eaten and mummified sheep thigh, impaled on a nearly petrified willow skewer.

"Back then, I didn't know a Clovis point from a Buck knife, but I sure as heck know a lamb kebab when I see one."

He was also relatively certain that all of these items -- particularly the primitive figurine -- were highly unusual coming from so far below the surface. Ybargoitia sent the drill crew home, gathered up everything he'd found into his lunch box, and called the Treasure Valley Community College in Ontario, Oregon. He was referred to the Cultural Anthropology Department.

"When Buzzy showed me those things, I about fell out of my chair," said Dr. Benton Schrall, the department head. "North American artifacts aren't exactly my field. Still, I recognized immediately that he had stumbled onto something very significant."

That afternoon, Dr. Schrall e-mailed a colleague at Washington State University in Pullman, who put him in touch with Dr. Lawrence Riggs, the chairman of WSU's Archaeology Department. Said Dr. Schrall, "When I described to Larry what I had, right there on my desk, the first thing out of his mouth was, 'Whatever you do, don't tell any Indians about it!' I guess he got burned pretty bad on that Kennewick Man deal."

With two of his brightest grad students in tow, Dr. Riggs drove to Ontario the next day. As soon as he saw the artifacts, he knew exactly what he would be doing for the next several summers. "Clovis points in Idaho? And from 7 meters down! That alone is an archaeologist's dream, without even considering the totem figure."

Fearful of letting that figurine out of his sight, Dr. Riggs shaved a thin specimen from the bottom of one tiny foot and sent it to Le Duchamp Laboratoire in Lyons, France, a world leader in intra-spectral comparative analysis. He then spent the next six weeks organizing what would become the largest -- and most covert -- archaeological dig in Idaho's history. Even Ybargoitia was sworn to secrecy.

"Larry Riggs had me sign a paper that said as long as I didn't tell anyone else about what I'd found, his university would foot the bill for another well. He came down on spring break, along with a nine-seater van full of students, and they set up a cyclone fence around that spot and put a tent over the hole. It about killed me that I couldn't tell anybody. It was like getting to be in a movie or something, only I couldn't even let my friends know I was in it."

The excavation proper began after the semester ended on May 21, 2005, and by Labor Day of that year, Dr. Riggs had confirmed what his instincts had been telling him since he first saw the figurine. Le Duchamp lab sent him their analysis of the sample in early July. They had tested the specimen three times, and for further confirmation, they had sent a portion to another independent laboratory in Quebec to verify their findings. There could be no mistake: The sample was from a unique soapstone found only in a region of northern Spain, on the southern slopes of the Pyrenees Mountains.

It took 10 weeks of excruciatingly detailed soil removal for the team to get down as far as the drill bit had reached, but at a depth of just under 8 meters -- the investigators came across a strata of soot and charcoal, indicating the remains of an ancient campfire. Within a 5-meter radius of that fire pit, they uncovered a dozen more spear tips -- sophisticated Clovis points, all of them -- the gnawed bones of several seemingly domestic sheep, a shredded remnant of what appeared to be a leather drinking sack (a bota), and a human skull.

By summer's end, Dr. Riggs had circumstantial evidence that early humans had migrated to this hemisphere from the Iberian Peninsula. But most astounding was the level at which this body of evidence had been found. The geological strata in which the items lay dated from a very narrow (and little understood) time frame known as the Proto-Paleolithic, indicating that human beings had put their footprint on the New World 40,000 years before anyone had previously believed possible.

Even more momentous were the "associative implicatory collateral traces," as they are called in the field of paleoanthropology, which implied that wherever these people came from, they brought their sheep with them.