Eid al-Adha

| Eid al-Adha | |

|---|---|

National Eidgah decorated for Eid al-Adha celebration in Bangladesh | |

| Official name | Eid al-Adha |

| Observed by | List

|

| Type | Islamic |

| Significance | Commemoration of Abraham (Ibrahim)'s willingness to sacrifice his son in obedience to a command from God |

| Celebrations | During the Eid al-Adha celebration, Muslims greet each other by saying 'Eid Mubarak', which is Arabic for "Blessed Eid". |

| Observances | Eid prayers, animal slaughter, charity, social gatherings, festive meals, gift-giving |

| Begins | 10 Dhu al-Hijja |

| Ends | 13 Dhu al-Hijja |

| Date | 10 Dhu al-Hijjah |

| 2024 date | 16 June - 20 June (Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan)[1] 16 June – 18 June (Saudi Arabia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan)[2][3][4] 17 June (Indonesia)[5] 18 June - 20 June (United Kingdom, Brunei, Singapore, Japan, Morocco, Malaysia)[6] |

| 2025 date | 6 June – 10 June [7] |

| Related to | Hajj; Eid al-Fitr |

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic culture |

|---|

| Architecture |

| Art |

| Clothing |

| Holidays |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Theatre |

Eid al-Adha (/ˌiːd əl ˈɑːdə/ EED əl AH-də; Arabic: عيد الأضحى, romanized: ʿĪd al-ʾAḍḥā, IPA: [ˈʕiːd alˈʔadˤħaː]) or the Feast of Sacrifice is the second of the two main holidays celebrated in Islam (the other being Eid al-Fitr). In Islamic tradition, it honours the willingness of Abraham to sacrifice his son as an act of obedience to God's command. Depending on the narrative, either Ishmael or Isaac is referred to with the honorific title "Sacrifice of God".[11] However, before Abraham could sacrifice his son in the name of God, and because of his willingness to do so, God provided him with a lamb to sacrifice in his son's place. In commemoration of this intervention, animals such as lambs are sacrificed. The meat of the sacrificed animal is divided into three portions: one part of the meat is consumed by the family that offers the animal, one portion is for friends and relatives, while the rest of the meat is distributed to the poor and the needy. Sweets and gifts are given, and extended family members typically visit and are welcomed.[12] The day is also sometimes called the "Greater Eid" (Arabic: العيد الكبير, romanized: al-ʿĪd al-Kabīr).[13]

In the Islamic lunar calendar, Eid al-Adha falls on the tenth day of Dhu al-Hijja and lasts for four days. In the international (Gregorian) calendar, the dates vary from year to year, shifting approximately 11 days earlier each year.

Pronunciation[edit]

Eid al-Adha is pronounced Eid al-Azha and Eidul Azha, primarily in Iran and influenced by the Persian language like the Indian subcontinent; /ˌiːd əl ˈɑːdə, - ˈɑːdhɑː/ EED əl AH-də, - AHD-hah; Arabic: عيد الأضحى, romanized: ʿĪd al-ʾAḍḥā, IPA: [ʕiːd al ˈʔadˤħaː].[14]

Etymology[edit]

The Arabic word عيد (ʿīd) means 'festival', 'celebration', 'feast day', or 'holiday'. It itself is a triliteral root عيد (ʕ-y-d) with associated root meanings of "to go back, to rescind, to accrue, to be accustomed, habits, to repeat, to be experienced; appointed time or place, anniversary, feast day".[15][16] Arthur Jeffery contests this etymology, and believes the term to have been borrowed into Arabic from Syriac, or less likely Targumic Aramaic.[17]

The holiday is called عيد الأضحى (Eid-al-Adha) or العيد الكبير (Eid-al-Kabir) in Arabic.[18] The words أضحى (aḍḥā) and قربان (qurbān) are synonymous in meaning 'sacrifice' (animal sacrifice), 'offering' or 'oblation'. The first word comes from the triliteral root ضحى (ḍaḥḥā) with the associated meanings "immolate; offer up; sacrifice; victimize".[19] No occurrence of this root with a meaning related to sacrifice occurs in the Qur'an[15] but in the Hadith literature. Assyrians and other Middle Eastern Christians use the term to mean the Eucharistic host. The second word derives from the triliteral root قرب (qaraba) with associated meanings of "closeness, proximity... to moderate; kinship...; to hurry; ...to seek, to seek water sources...; scabbard, sheath; small boat; sacrifice".[16] Arthur Jeffery recognizes the same Semitic root, but believes the sense of the term to have entered Arabic through Aramaic.[17]

Origin[edit]

One of the main trials of Abraham's life was to receive and obey the command of God to slaughter his beloved son. According to the narrative, Abraham kept having dreams that he was sacrificing his son. Abraham knew that this was a command from God and he told his son, as stated in the Quran,

"Oh son, I keep dreaming that I am slaughtering you". he replied, "Father, do what you are ordered to do."

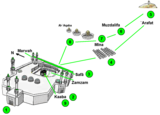

Abraham prepared to submit to the will of God and to slaughter his son as an act of faith and obedience to God.[20] During the preparation, Iblis (Satan) tempted Abraham and his family by trying to dissuade them from carrying out God's commandment, and Abraham drove Iblis away by throwing pebbles at him. In commemoration of their rejection of Iblis, stones are thrown during Hajj rites at symbolic pillars, symbolising the place at which Iblis tried to dissuade Abraham.[21]

Acknowledging that Abraham was willing to sacrifice what is dear to him, God honoured both Abraham and his son. Angel Gabriel (Jibreel) called Abraham, "O' Ibrahim, you have fulfilled the revelations." and a ram from heaven was offered by Angel Gabriel to prophet Abraham to slaughter instead of his son. Many Muslims celebrate Eid al Adha to commemorate both the devotion of Abraham and the survival of his son Ishmael.[22][23][24]

This story is known as the Akedah in Judaism (Binding of Isaac) and originates in the Torah,[25] the first book of Moses (Genesis, Ch. 22). The Quran refers to the Akedah as follows:[26]

100 My Lord! Bless me with righteous offspring."

101 So We gave him good news of a forbearing son.

102 Then when the boy reached the age to work with him, Abraham said, "O my dear son! I have seen in a dream that I ˹must˺ sacrifice you. So tell me what you think." He replied, "O my dear father! Do as you are commanded. Allah willing, you will find me steadfast."

103 Then when they submitted ˹to Allah's Will˺, and Abraham laid him on the side of his forehead ˹for sacrifice˺,

104 We called out to him, "O Abraham!

105 You have already fulfilled the vision." Indeed, this is how We reward the good-doers.

106 That was truly a revealing test.

107 And We ransomed his son with a great sacrifice,

108 and blessed Abraham ˹with honourable mention˺ among later generations:

109 "Peace be upon Abraham."

110 This is how We reward the good-doers.

111 He was truly one of Our faithful servants.

112 We ˹later˺ gave him good news of Isaac—a prophet, and one of the righteous.

The word "Eid" appears once in Al-Ma'ida, the fifth surah of the Quran, with the meaning "a festival or a feast".[27]

Ritual slaughter[edit]

The tradition for Eid al-Adha involves slaughtering an animal and sharing the meat in three equal parts – for family, for relatives and friends, and for poor people. The goal is to make sure every Muslim gets to eat meat.[28][29] However, there is a dissent among Muslim scholars regarding the obligatory nature of this sacrifice. While some scholars, such as Al-Kasani, categorise the sacrifice as obligatory (wāǧib), others regard it only as an "established custom" (sunna mu'akkada).[30] Alternatives such as charitable donations or fasting have been suggested to be permissible by several faqih.[31]

Prayers[edit]

Devotees offer the Eid al-Adha prayers at the mosque. The Eid al-Adha prayer is performed any time after the sun completely rises up to just before the entering of Zuhr time, on the tenth of Dhu al-Hijja. In the event of a force majeure (e.g. natural disaster), the prayer may be delayed to the 11th of Dhu al-Hijja and then to the 12th of Dhu al-Hijja.[32]

Eid prayers must be offered in congregation. Participation of women in the prayer congregation varies from community to community.[33] It consists of two rakats (units) with seven takbirs in the first Raka'ah and five Takbirs in the second Raka'ah. For Shia Muslims, Salat al-Eid differs from the five daily canonical prayers in that no adhan (call to prayer) or iqama (call) is pronounced for the two Eid prayers.[34][35] The salat (prayer) is then followed by the khutbah, or sermon, by the Imam.[36]

At the conclusion of the prayers and sermon, Muslims embrace and exchange greetings with one another (Eid Mubarak), give gifts and visit one another. Many Muslims also take this opportunity to invite their friends, neighbours, co-workers and classmates to their Eid festivities to better acquaint them about Islam and Muslim culture.[37]

Traditions and practices[edit]

During Eid al-Adha, distributing meat amongst the people, chanting the takbir out loud before the Eid prayers on the first day and after prayers throughout the four days of Eid, are considered essential parts of this important Islamic festival.[38]

The takbir consists of:[39]

الله أكبر الله أكبر الله أكبر |

Allāhu akbar, Allāhu akbar, Allāhu akbar |

Adults and children are expected to dress in their finest clothing to perform Eid prayer in a large congregation in an open waqf ("stopping") field called Eidgah or mosque. Affluent Muslims who can afford it sacrifice their best halal domestic animals (usually a camel, goat, sheep, or ram depending on the region) as a symbol of Abraham's willingness to sacrifice his only son.[40] The sacrificed animals, called aḍḥiya (Arabic: أضحية), known also by the Perso-Arabic term qurbāni, have to meet certain age and quality standards or else the animal is considered an unacceptable sacrifice.[41] In Pakistan alone, roughly 7.5 million animals are sacrificed on Eid days, costing an estimated $3 billion in 2011 (equivalent to $4.16 billion in 2023).[42][43]

The meat from the sacrificed animal is preferred to be divided into three parts. The family retains one-third of the share; another third is given to relatives, friends, and neighbors; and the remaining third is given to the poor and needy.[40]

Muslims wear their new or best clothes. People cook special sweets, including ma'amoul (filled shortbread cookies) and samosas. They gather with family and friends.[32]

In the Gregorian calendar[edit]

While Eid al-Adha is always on the same day of the Islamic calendar, the date on the Gregorian calendar varies from year to year since the Islamic calendar is a lunar calendar and the Gregorian calendar is a solar calendar. The lunar calendar is approximately eleven days shorter than the solar calendar.[44][b] Each year, Eid al-Adha (like other Islamic holidays) falls on one of about two to four Gregorian dates in parts of the world, because the boundary of crescent visibility is different from the International Date Line.[45]

The following list shows the official dates of Eid al-Adha for Saudi Arabia as announced by the Supreme Judicial Council. Future dates are estimated according to the Umm al-Qura calendar of Saudi Arabia.[8] The Umm al-Qura calendar is just a guide for planning purposes and not the absolute determinant or fixer of dates. Confirmations of actual dates by moon sighting are applied on the 29th day of the lunar month prior to Dhu al-Hijja[46] to announce the specific dates for both Hajj rituals and the subsequent Eid festival. The three days after the listed date are also part of the festival. The time before the listed date the pilgrims visit Mount Arafat and descend from it after sunrise of the listed day.[47]

In many countries, the start of any lunar Hijri month varies based on the observation of new moon by local religious authorities, so the exact day of celebration varies by locality.

| Islamic year | Gregorian date |

|---|---|

| 1400 | 20 October 1980 |

| 1401 | 8 October 1981 |

| 1402 | 27 September 1982 |

| 1403 | 17 September 1983 |

| 1404 | 5 September 1984 |

| 1405 | 26 August 1985 |

| 1406 | 15 August 1986 |

| 1407 | 4 August 1987 |

| 1408 | 25 July 1988 |

| 1409 | 13 July 1989 |

| 1410 | 2 July 1990 |

| 1411 | 22 June 1991 |

| 1412 | 11 June 1992 |

| 1413 | 31 May 1993 |

| 1414 | 20 May 1994 |

| 1415 | 9 May 1995 |

| 1416 | 29 April 1996 |

| 1417 | 17 April 1997 |

| 1418 | 7 April 1998 |

| 1419 | 27 March 1999 |

| 1420 | 16 March 2000 |

| 1421 | 5 March 2001 |

| 1422 | 22 February 2002 |

| 1423 | 11 February 2003 |

| 1424 | 1 February 2004 |

| 1425 | 20 January 2005 |

| 1426 | 10 January 2006 |

| 1427 | 30 December 2006 |

| 1428 | 20 December 2007 |

| 1429 | 8 December 2008 |

| 1430 | 27 November 2009 |

| 1431 | 16 November 2010 |

| 1432 | 6 November 2011 |

| 1433 | 26 October 2012 |

| 1434 | 15 October 2013 |

| 1435 | 5 October 2014 |

| 1436 | 24 September 2015 |

| 1437 | 12 September 2016 |

| 1438 | 1 September 2017 |

| 1439 | 20 August 2018 |

| 1440 | 11 August 2019 |

| 1441 | 31 July 2020 |

| 1442 | 20 July 2021 |

| 1443 | 9 July 2022 |

| 1444 | 28 June 2023 |

| 1445 | 16 June 2024 |

| 1446 | 6 June 2025 (calculated) |

| 1447 | 26 May 2026 (calculated) |

| 1448 | 16 May 2027 (calculated) |

| 1449 | 4 May 2028 (calculated) |

| 1450 | 23 April 2029 (calculated) |

| 1451 | 13 April 2030 (calculated) |

| 1452 | 2 April 2031 (calculated) |

| 1453 | 21 March 2032 (calculated) |

| 1454 | 11 March 2033 (calculated) |

| 1455 | 28 February 2034 (calculated) |

| 1456 | 17 February 2035 (calculated) |

| 1457 | 7 February 2036 (calculated) |

| 1458 | 26 January 2037 (calculated) |

| 1459 | 16 January 2038 (calculated) |

| 1460 | 5 January 2039 (calculated) |

| 1461 | 14 December 2039 (calculated) |

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^

Translation: Allah is the greatest, Allah is the greatest, Allah is the greatest

There is no god but Allah

Allah is greatest, Allah is greatest

and to Allah goes all praise.[32] - ^ Because the Hijri year differs by about 11 days from the AD year, Eid al-Adha can occur twice a year, in the year 1029, 1062, 1094, 1127, 1159, 1192, 1224, 1257, 1290, 1322, 1355, 1387, 1420, 1452, 1485, 1518, 1550, 1583, 1615, 1648, 1681, 1713, 1746, 1778, 1811, 1844, 1876, 1909, 1941, 1974, 2007, 2039, 2072, 2104, 2137, 2169, 2202, 2235, 2267 and 2300 (will continue to occur every 32 or 33 years).

References[edit]

- ^ Masalieva, Zhazgul (28 June 2023). "Как отметить Курман айт. Правила, условия и требования праздника". 24.kg. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ "Islamic Holidays, 2010–2030 (A.H. 1431–1452)". InfoPlease. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ "Курбан айт - 2023 в Казахстане: какого числа и как праздновать". Tengri News. 26 June 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ "В Туркменистане 28-29-30 июня будут отмечать Курбан байрам". Turkmen Portal. 27 May 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ Translation, Office of Assistant to Deputy Cabinet Secretary for State Documents & (12 September 2023). "Gov't Announces National Holidays for 2024". Sekretariat Kabinet Republik Indonesia. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ "Eid Al Adha 2023 in UK is on June 29". Morocco World News. 19 June 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ Hughes, David (18 July 2021). "When Eid al-Adha 2021 falls – and how long the festival lasts". inews.co.uk. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ a b "The Umm al-Qura Calendar of Saudi Arabia". Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "First day of Hajj confirmed as Aug. 9". Arab News. 1 August 2019. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ Bentley, David (9 August 2019). "When is the Day of Arafah 2019 before the Eid al-Adha celebrations?". Birmingham Mail. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ Firestone, Reuven (January 1990). Journeys in Holy Lands: The Evolution of the Abraham-Ishmael Legends in Islamic Exegesis. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0331-0.

- ^ "Id al-Adha". Oxford Islamic Studies Online. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ Haigh, Phil (31 July 2020). "What is the story of Eid al-Adha and why is it referred to as Big Eid?". Metro. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

Simply, Eid al-Adha is considered the holier of the two religious holidays and so it is referred to as 'Big Eid' whilst Eid al Fitr can be known as 'Lesser Eid'. Eid al-Kabir means 'Greater Eid' and is used in Yemen, Syria, and North Africa, whilst other translations of 'Large Eid' are used in Pashto, Kashmiri, Urdu and Hindi. This distinction is also known in the Arab world, but by calling 'Bari Eid' bari, this Eid is already disadvantaged. It is the 'other Eid'. 'Bari Eid', or Eid-ul-Azha, has the advantage of having two major rituals, as both have the prayer, but it alone has a sacrifice. 'Bari Eid' brings all Muslims together in celebrating Hajj, which is itself a reminder of the Abrahamic sacrifice, while 'Choti Eid' commemorates solely the end of the fasting of Ramazan.

- ^ "Definition of Eid al-Adha | Dictionary.com". www.dictionary.com. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ a b Oxford Arabic Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2014. ISBN 978-0-19-958033-0.

- ^ a b Badawi, Elsaid M.; Abdel Haleem, Muhammad (2008). Arabic–English Dictionary of Qur'anic Usage. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-14948-9.

- ^ a b Jeffery, Arthur (2007). The Foreign Vocabulary of the Qur'ān. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15352-3.

- ^ Noakes, Greg (April–May 1992). "Issues in Islam, All About Eid". Washington Report on Middle East Affairs. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ Team, Almaany. "Translation and Meaning of ضحى In English, English Arabic Dictionary of terms Page 1". almaany.com. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ Bate, John Drew (1884). An Examination of the Claims of Ismail as Viewed by Muḥammadans. BiblioBazaar. p. 2. ISBN 978-1117148366. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

Ishmael sacrifice.

- ^ Firestone, Reuven (1990). Journeys in Holy Lands: The Evolution of the -Ishmael Legends in Islamic Exegesis. SUNY Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0791403310.

- ^ "The Significance of Hari Raya Aidiladha". muslim.sg. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ^ Elias, Jamal J. (1999). Islam. Routledge. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-415-21165-9. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Muslim Information Service of Australia. "Eid al – Adha Festival of Sacrifice". Missionislam.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ Stephan Huller, Stephan (2011). The Real Messiah: The Throne of St. Mark and the True Origins of Christianity. Watkins; Reprint edition. ISBN 978-1907486647.

- ^ Fasching, Darrell J.; deChant, Dell (2011). Comparative Religious Ethics: A Narrative Approach to Global Ethics. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1444331332.

- ^ Quran 5:114 -The Clear Quran— Jesus, son of Mary, prayed, "O Allah, our Lord! Send us from heaven a table spread with food as a feast for us—the first and last of us—and as a sign from You. Provide for us! You are indeed the Best Provider." Quran 5:114 -Sahih International— Said Jesus, the son of Mary, "O Allāh, our Lord, send down to us a table [spread with food] from the heaven to be for us a festival for the first of us and the last of us and a sign from You. And provide for us, and You are the best of providers."

- ^ "Qurbani Meat Distribution Rules". Muslim Aid.

- ^ "Qurbani Meat Distribution Rules". islamicallrounder. 30 March 2022.

- ^ Hawting, Gerald (2007). "The Juristic Dispute about the Legal Status of the Animal Offerings on the Feast of Sacrifices". In Christmann, Andreas; Gleave, Robert (eds.). Studies in Islamic Law: A Festschrift for Colin Imber. Journal of Semitic Studies Supplement. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 123–142. ISBN 978-0-19-953491-3.

- ^ Leaman, Oliver; Shaikh, Zinnira (2022). "Heresy or Moral Imperative? Islamic Perspectives on Veganism". Routledge Handbook of Islamic Ritual and Practice. Routledge Handbooks. Abingdon, New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 446–447. ISBN 978-0-367-49123-9.

- ^ a b c H. X. Lee, Jonathan (2015). Asian American Religious Cultures [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 357. ISBN 978-1598843309.

- ^ Asmal, Fatima (6 July 2016). "South African women push for more inclusive Eid prayers". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 5 September 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ "Sunnah during Eid ul Adha according to Authentic Hadith". 13 November 2010. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2011 – via Scribd.

- ^ حجم الحروف – Islamic Laws : Rules of Namaz » Adhan and Iqamah. Retrieved 10 August 2014

- ^ "Eid ul-Fitr 2020: How to say Eid prayers". Hindustan Times. 23 May 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ "The Significance of Eid". Isna.net. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ McKernan, Bethan (29 August 2017). "Eid al-Adha 2017: When is it? Everything you need to know about the Muslim holiday". .independent. Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ^ "Eid Takbeers – Takbir of Id". Islamawareness.net. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ a b Buğra Ekinci, Ekrem (24 September 2015). "Qurban Bayram: How do Muslims celebrate a holy feast?". dailysabah. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018.

- ^ Cussen, V.; Garces, L. (2008). Long Distance Transport and Welfare of Farm Animals. CABI. p. 35. ISBN 978-1845934033.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Ahsan Butt (16 November 2010). "Bakra Eid: The cost of sacrifice". Asian Correspondent. Archived from the original on 28 December 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ Hewer, Chris (2006). Understanding Islam: The First Ten Steps. SCM Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0334040323.

he Gregorian calendar.

- ^ Staff, India com (30 July 2020). "Eid al-Adha or Bakrid 2020 Date And Time: History And Significance of The Day". India News, Breaking News, Entertainment News | India.com. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ "Eid al-Adha 2016 date is expected to be on September 11". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ^ "Mount Ararat | Location, Elevation, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

External links[edit]

Media related to Eid al-Adha at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Eid al-Adha at Wikimedia Commons- Muttaqi, Shahid ‘Ali. "The Sacrifice of 'Eid al-Adha'".

- Abraham in Islam

- Animal festival or ritual

- Druze festivals and holy days

- Eid (Islam)

- Hajj

- Islamic holy days

- Islamic terminology

- Public holidays in Algeria

- Public holidays in Azerbaijan

- Public holidays in India

- Public holidays in Pakistan

- Public holidays in Bangladesh

- Public holidays in Myanmar

- Public holidays in Singapore

- Public holidays in Sri Lanka

- Public holidays in Turkey

- Public holidays in Malaysia