Islamic manuscripts

Islamic manuscripts had a variety of functions ranging from Qur'anic recitation to Scientific notation. These manuscripts were produced in many different ways depending on their use and time period. Parchment (vellum) was a common way to produce manuscripts.[1] Manuscript creators eventually transitioned to using paper in later centuries with the diffusion of paper making in the Islamic empire. When Muslims encountered paper in Central Asia, its use and production spread to Iran, Iraq, Syria, Egypt, and North Africa during the 8th century.[2]

Scripts[edit]

.jpg/300px-Folio_from_a_Koran_(8th-9th_century).jpg)

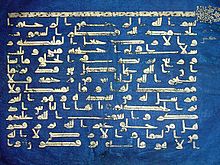

The development of scripts in the Islamic empire, demonstrates the transition from an oral culture to convey information to a written form. Traditionally speaking in the Islamic empire, Arabic calligraphy was the common form of recording texts. Calligraphy is the practice or art of decorative handwriting.[3] The demand for calligraphy in the early stages of the Islamic empire (circa 7–8th century) can be attributed to a need to produce Qur'an manuscripts. During the Umayyad period, Kufic scripts were typically seen in Qur'an manuscripts.[3]

However, Arabic was only one of the scripts used for recording religious manuscripts. In the Indian subcontinent, for example, Nizari Ismailis utilized the Khwajah Sindhi (Khojki) script, which was closely associated with their identity.[4] The specific form of this script was exclusively used by Nizari Ismailis, who were known as Khwajahs or Khojas. Recording religious literature in this script had the added benefit of preserving it from potentially hostile eyes.

Genres[edit]

Islamic manuscripts include variety of topics such as religion, medicine, astrology, and literature.

Religious Manuscripts[edit]

A common religious manuscript would be a copy of the Qur'an, which is the sacred book of Islam. The Qur'an is believed by Muslims to be a divine revelation (the word of god) to Muhammad, revealed to him by Archangel Gabriel.[5] Qur'anic manuscripts can vary in form and function. Certain manuscripts were larger in size for ceremonial purposes, others being smaller and more transportable. An example of a Qur'an manuscript is the Blue Qur'an. The Blue Qur'an is ceremonial in nature, which a Hafiz would utilize. It has gold Kufic script, on parchment dyed blue with indigo.[6] Many Qur'an manuscripts are divided into 30 equal sections (juz) to be able to be read over the course of 30 days.[7] The Chinese practice of writing on paper, presented to the Islamic world around the 8th century, enabled Qur'ans to begin to be written on paper. The decrease in production costs of Qur'an manuscripts due to the transition from parchment to paper enabled Qur'ans to be utilized more frequently for personal use/worship, rather than just ceremonial settings.[3]

Within the Nizari Ismaili Community, manuscripts were recorded in the Khwajah Sindhi (Khojki) script, as mentioned above. A common type of literature recorded in this script is known as Ginans. These are commonly in the form of devotional hymns recited by members of the community. The script also preserves other types of religious literature, such as songs of devotions in praise of Prophet Muhammed and legends about the Prophets.[4]

Evolution of Qur'anic Calligraphy and Technique[edit]

Manuscripts of the Qu'ran have been created and copied since the Umayyad period (661–750.)[8] Over the course of this period, copies of Qur'anic manuscripts were produced in Damascus and were named the "Damascus papers."[8] Some parts of the Damascus Papers contained hijazi script which was unique to each calligrapher's writing style.[8] Hijazi script disregarded the use of short vowels and was created to serve as a memory aid to reciters.[8] Manuscripts with Hijazi script also utilized the rules of scripto continua and displayed no decoration or ornamentation.[9] Under the reign of Umayyad caliph, Abd-al-Malik (685–705), Qur'anic script was standardized and inserted onto other surfaces such as marble as a way to promote Arabic in the region.[8] One example of marble inscription is seen inside the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem.[8] When paper-making set its course towards central Asia, paper became the preferred material setting for Qur'anic manuscripts. The use of paper amplified the development of new writing styles and motivated calligraphers to heighten the manuscripts' aesthetic appeal. Kufic script had been used as the main style of scripture until about 1200. After[9] the turn of the 13th century, calligraphers began to prefer writing styles such as naskh to transcribe the Qu'ran.[8] Before the fourteenth century, calligraphers were responsible for both the text and illumination of Qur'anic manuscripts until the artwork became more complex and required its own specialist.[8]

Structure and Order of Qur'anic Manuscripts[edit]

In the making of Qur'anic manuscripts, early calligraphers used a strict set of geometric rules. For example, each page had a space reserved for writing which was divided into perfectly equal and parallel lines depending on thickness of the pen.[10] A set of key ratios was also used to determine the box's width and height.[10] After the structure of the text box was determined, calligraphers followed an interline system to write out the script.[10] Early Qur'anic manuscripts did not have a direct textual structure. To amplify oration and make recitation easier, illuminators created a decorative vocabulary. At first, the illuminators differentiated each surah by pairing it with a unique geometric band.[8] Subsequently, a more complex system was put in place in order to organize the Qur'an's contents and help individuals read and recite the text. This system included motifs (aya), chapters (surah), and primary divisions (juz) that are seen between each thirty sections and organize the singular text into different parts.[8] The Qur'an now contains 114 surahs with a range of three to 268 verses.[8]

Evolution of Illumination[edit]

During the recitation of Qur'anic manuscripts, the frontispiece was presented to the audience in order to display the beautiful illumination. These illuminations usually use geometry, and nature as inspiration and don't display any sort of iconography due to the values of Islam.[11] Early illuminators had to create the perfect sense of symbolism and ornamentation to represent each section of text while keeping the text as the main focal point.[11] In the eighth century, when the Qur'an was first produced as a codex, ornamentation was already included in the design.[8] The entire frontispiece of the Qur'an usually contained illumination as well as the borders of the first few folios, the last folios, and the titles of each chapter in the text.[8] The use of illuminated medallions also became popular after the tenth century to indicate each fifth and tenth verse within the text.[8] Around the eleventh century, only the first and last folios out of the entire text were illuminated. The illuminations were typically applied in gold and incorporated geometric and vegetal designs.[8] During the reign of the Mamluk and Ilkhanid dynasties (1250–1517), paper became more accessible and allowed for the production of larger scale Qur'ans.[8] This influenced illuminators to add more complex designs and new motifs. Qur'anic manuscripts produced by Mamluks were noted for gilded foliate scrollwork as well as star-shaped and hexagonal motifs.[8] The Ilkhanid dynasty was responsible for adapting their geometric vocabulary to different sized manuscripts and sense of lavishness in design.[8] The Timurid dynasty (1370–1507) introduced a style of illumination that included fine gilded leaves and stems, red florets, and diamond shaped medallions on a dark-blue background.[8] An example of this style of illumination is seen in this single-volume Qur'an that was made between 1480 and 1500. Manuscripts from the Safavid dynasty (1500–1700) is known for their fine golden and floral scroll illuminations with lapis backgrounds.[8] Additionally, the Safavid dynasty is also known for the Shiraz manuscripts which were large in size and elaborate in design.[8] Illuminators from the Ottoman Empire (1400–1700) were influenced by Timurid illumination and followed their gold and blue floral style.[8] Ottoman illuminators also incorporated rose, hyacinth, and tulip motifs into their illuminations. The Ottomans also built a manufacturing studio in Istanbul where illuminated Qur'ans were produced into the beginning of the twentieth century.[8]

Scientific Manuscripts[edit]

Many early illustrated Arabic manuscripts are affiliated with scientific subjects. Scientific manuscripts discuss a variety of topics including but not limited to astronomy, astrology, anatomy, botany, and zoology.[12] The development of early illustrated scientific manuscripts began under the Islamic Abbasid dynasty in Baghdad in approximately the mid-8th century. The development of new scientific work starting to translation of old Greek scientific and learned works, and the make pure original scholarship in science, medicine, and philosophy in Arabic.[13] An example of an Arabic scientific manuscript is the Book of the Fixed Stars by Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi. This manuscript is a catalog of stars and their constellations, commissioned by the patron the Buyid prince Adud al-Dawla.[13] The Book of the Fixed Stars based most of its content on Ptolemy's Mathēmatikē Syntaxis (Almagest), which was translated from Greek to Arabic during the 9th century. Al-Sufi's included his own observations of Ptolemy's material into this manuscript as well.[14]

The Scientific Manuscripts of Timbuktu[edit]

One of the most significant examples of scientific Islamic manuscripts comes from the Timbuktu Manuscripts.[15] The creation of these manuscripts range from the 13th to the 20th century, with most of them being made during the Mali Empire (1230–1672).[16] Within these manuscripts, there is discussion of several scientific concepts including mathematics, astronomy, astrology, and medicine. Although these are scientific manuscripts, many of them include poetic structure. One example of these scientific manuscripts is Manuscript no. 2262, a work that discusses ideas about astronomy. This manuscript discusses the intersection between solar and lunar calendars. More specifically, this manuscript instructs the reader on how to determine January first of the Islamic Lunar Year 1023. Additionally, the manuscript discusses the process of determining whether or not it is leap year.[17] Another example is Manuscript no. 1045, entitled by scholars as "The Treatment of Illnesses, Internal and External."[18] In this manuscript, the author discusses medical ideas such as: the use of plants for treating illnesses, the use of minerals and their medicinal powers, and the use of animal organs in certain healing processes. Timbuktu Manuscripts are unique due to the sheer volume of manuscripts discovered and their wide range of concepts including concepts of philosophy that contradicted common ideas about Islamic framework.[19]

Collections[edit]

Khuda Bakhsh Oriental Public Library[edit]

The Khuda Bakhsh Oriental Library has a collection of 25,000 Islamic Manuscripts.[20][21][22][23][24] including Padshahnama,Tareek ke khandan e timuriya, Divān of Hafez, Safinatul Auliya and Sahih al-Bukhari,[22] hand-transcribed by Shaykh Muhammad ibn Yazdan Bakhsh Bengali in Ekdala, eastern Bengal. The manuscript was a gift to the Sultan of Bengal Alauddin Husain Shah.[25] It is also the only library in the world to have the original manuscripts from the Caliphate of Cordoba. It presently has the best collection of Islamic manuscripts.[26][27]

Mamma Haidara Commemorative Library[edit]

The Mamma Haidara Commemorative Library is a collection of thousands of Islamic manuscripts from Timbuktu.[28][29] They were moved to Bamako for safekeeping due to the Mali War.[28]

The Zaydani Collection[edit]

The Zaydani Library or Zaydani Collection (Arabic: الخزانة الزيدانية) is a collection of manuscripts belonging to Sultan Zidan Abu Maali of the Saadi dynasty that is located at El Escorial in Spain.[30]

Cambridge University Library[edit]

In the 1630s Cambridge University founded a Professorship in Arabic. The Cambridge University Library collection started with the donation of the Quran by William Bedwell. Since then it has grown to over 5,000 works. It includes collections of Thomas Erpenius, J.L.Burckhardt, E.H.Palmer and E.G. Browne.[31]

The British Library[edit]

The British Library hold a collection of almost 15,000 works in 14,000 volumes. In 1982 the collections of the India Office Library were transferred to the British library.[32]

University of Michigan[edit]

One of the largest collections in North America is at the University of Michigan which holds 1,800 text contained in over 1,100 volumes.[33]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan. (2001). Paper before print : the history and impact of paper in the Islamic world. Yale University Press. pp. 12. ISBN 0300089554. OCLC 830505350.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan. (2001). Paper before print : the history and impact of paper in the Islamic world. Yale University Press. pp. 47. ISBN 0300089554. OCLC 830505350.

- ^ a b c George, Alain (2017-06-20), "The Qurʾan, Calligraphy, and the Early Civilization of Islam", A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 109–129, doi:10.1002/9781119069218.ch4, ISBN 9781119069218

- ^ a b Asani, Ali (2002). "Ecstasy and Enlightenment: The Ismaili Devotional Literature of South Asia". The Institute of Ismaili Studies: 144.

- ^ "Early Qur'ans (8th–Early 13th Century)". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M. (2015-01-01). "The Blue Koran Revisited". Journal of Islamic Manuscripts. 6 (2–3): 196–218. doi:10.1163/1878464x-00602005. ISSN 1878-4631.

- ^ Ekhtiar, Maryam. "Early Qur'ans (8th–Early 13th Century)". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Türk ve İslâm Eserleri Müzesi (2016). The art of the Qurʼan : treasures from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts. Massumeh Farhad, Simon Rettig, François Déroche, Zeren Tanındı, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. Washington, DC. ISBN 978-1-58834-578-3. OCLC 953576432.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b The Oxford handbook of Qur'anic studies. Mustafa Akram Ali Shah, M. A. Abdel Haleem (1st ed.). Oxford. 2020. ISBN 978-0-19-182208-7. OCLC 1158924611.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c George, Alain; جورج, آلان (2007). "The Geometry of Early Qur'anic Manuscripts / التسليم الهندسي للمخطوطات القرآنية المبكرة". Journal of Qur'anic Studies. 9 (1): 78–110. ISSN 1465-3591. JSTOR 25728237.

- ^ a b Hussain, Tajammul. “Roads to Paradise: The Art of the Illumination of the Qur’an.” (2016). https://www.themathesontrust.org/papers/art/Tajammul-Roads.pdf

- ^ Hoffman, Eva R. 2000. The Beginnings of the Illustrated Arabic Book: An Intersection between Art and Scholarship. In Muqarnas: An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic World, XVII, pg.38.

- ^ a b Hoffman, Eva R. 2000. The Beginnings of the Illustrated Arabic Book: An Intersection between Art and Scholarship. In Muqarnas: An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic World, XVII, pg. 44.

- ^ Hoffman, Eva R. 2000. The Beginnings of the Illustrated Arabic Book: An Intersection between Art and Scholarship. In Muqarnas: An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic World, XVII, pg. 47.

- ^ "Timbuktu Manuscripts Apparently Escaped Burning". AAAS Articles DO Group. 2021-10-18. doi:10.1126/article.26472. S2CID 239597685. Retrieved 2022-11-22.

- ^ The meanings of Timbuktu. Shamil Jeppie, Souleymane Bachir Diagne. Cape Town: HSRC Press in association with CODESRIA. 2008. ISBN 978-0-7969-2204-5. OCLC 184829143.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Alli, AF (2009-11-12). "Timbuktu's Scientific Manuscript Heritage: The Reopening of an Ancient Vista?". Journal for the Study of Religion. 22 (1). doi:10.4314/jsr.v22i1.47785. ISSN 1011-7601.

- ^ "Ahmad Ibn Umar al Dhaki", Benezit Dictionary of Artists, Oxford University Press, 2011-10-31, doi:10.1093/benz/9780199773787.article.b00001605, retrieved 2022-11-22

- ^ Djian, Jean-Michel (2012). The manuscripts of Timbuktu. Christopher Wise, J.-M. G. Le Clézio, Souleymane Bachir Diagne (First AWP English ed.). Trenton: Africa World Press. pp. 70–97. ISBN 978-1-56902-638-0. OCLC 1086487795.

- ^ "Khuda Baksh oriental Public Library". Incredible India. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ "Khuda Baksh Oriental Library". Bihar Tourism. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ a b Chavan, Akshay (May 2, 2019). "Khuda Bakhsh Library: Patna's Treasure House". Peepul Tree. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ "Historical Perspective". KB Library. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ "Treasure Trove of Manuscripts". Deccan Herald. November 19, 2018. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ Mawlana Nur Muhammad Azmi. "2.2 বঙ্গে এলমে হাদীছ" [2.2 Knowledge of Hadith in Bengal]. হাদীছের তত্ত্ব ও ইতিহাস [Information and history of Hadith] (in Bengali). Emdadia Library. p. 24.

- ^ Majid, DR. Abdul. "The founder of the world-famous Oriental Public Library. (Paragraph 2 Line 5 - 6)". Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ AL, JAZEERA. "Khuda Bakhsh library's importance to the world". Al Jazeera. pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b "'Badass Librarians' Foil al Qaeda, Save Ancient Manuscripts". History. 2016-06-12. Retrieved 2022-10-20.

- ^ "The Mamma Haidara Memorial Library – Tombouctou Manuscripts Project". 2011-04-15. Archived from the original on 2011-04-15. Retrieved 2022-10-20.

- ^ Derenbourg, Hartwig (1844-1908) Auteur du texte (1928). Les Manuscrits arabes de l'Escurial. Tome III, Théologie. Géographie. Histoire / décrits d'après les notes de Hartwig Derenbourg ; revues et mises à jour par E. Lévi-Provençal.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Islamic Manuscripts". cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2021-08-09.

- ^ "Arabic manuscripts". The British Library. Retrieved 2021-08-10.

- ^ "Islamic Manuscripts". www.lib.umich.edu. Retrieved 2021-08-10.